I. Numbers in the Air

There are two stories about India’s air pollution that reveal radically different truths.

The first is a story of progress, told through government monitors. In September 2024, the National Clean Air Programme (NCAP) showed signs of victory: 95 out of 131 cities showing improvement, with 21 achieving more than 40% reduction in pollution levels. India, it seemed, was finally winning its war against dirty air.

The second is a story of despair, told through comprehensive scientific analysis. Satellites scanning the Indian atmosphere tracked the chemical signatures of pollution through entire columns of air. They found NO2 from vehicle exhaust rising 10% and SO2 from coal burning up 30% — the unmistakable fingerprints of fossil fuel combustion growing stronger year by year.

The satellites didn’t see a cleaner India. They saw a country where the fundamental sources of deadly air pollution—vehicles, factories, power plants—were burning more than ever.

Both stories are built on publicly accessible data. Both shape policy and public understanding.

Both can’t be true.

In 2019, India launched the NCAP, its most ambitious attempt to curb the public health crisis. It began with brutal honesty: the government admitted that this problem couldn’t be solved by individual cities fighting lonely battles. It identified around a hundred cities that had failed air quality standards for years.

The approach was comprehensive. The programme recognised that air doesn’t respect city boundaries—pollution from one city drifts to another. It required strategies at every administrative level: local bodies would implement solutions, and the central government would provide resources and oversight. Cities drafted detailed action plans. Every successful experiment was supposed to be shared. Every lesson learned passed on.

The investment matched the ambition. The central government committed ₹300 crores initially. By 2024, this grew to ₹9,650 crores—the largest coordinated investment India had ever made in fighting air pollution.

The target was bold but seemed achievable: reduce two major pollutants—PM10 and PM2.5—by 20-30% by 2024. It was benchmarked with cities like Beijing and Seoul that had shown such reductions were possible, cutting down by 35-40% in five years. Why can’t we?

And then, in 2022, with a few bureaucratic strokes, the programme’s fundamental promise was altered. More ambitious, they said.

To understand how this change transformed the programme, we need to visit one of its success stories.

II. Measuring Dust

When we called Surat’s NCAP nodal officer, it took us three tries to reach him. When Jwalant Naik finally answered, he was wrestling with a peculiar problem.

His city had received a national award for improving air quality in 2024. By every official measure, Surat was a success story. And then there was the metro.

“Surat is a developing city. Almost half the city is engulfed in metro construction, and it will remain so for many years to come,” Naik, an environmental engineer with the Surat Municipal Corporation, told us, with genuine worry in his voice.

This is a problem for Naik. Yes, the metro, once completed, could possibly take thousands of polluting vehicles off Surat’s roads. But right now, its construction threatened something more immediate: the city’s air quality.

Under NCAP, each city has to show a 15% reduction in air quality numbers every year. The construction dust from the metro will make it hard.

The stakes are high. 40 per cent of a city’s NCAP funding is directly linked to these air quality performance metrics. Fail to show progress, and the city loses its financial resources.

“So how will this happen?” he asks. “With this construction, would I ever be able to get a good AQI reading?”

The irony runs deep. A project meant to reduce pollution in the long run now threatens the city’s ability to show progress in the short term.

Surat has executed elaborate plans to stay on track.

Thirty-five massive mechanical sweepers prowl the streets at night, brushing and spraying water. Workers stand at construction sites with water hoses, fighting dust hour by hour. The city has paved over 4,000 kilometres of roads because unpaved roads are dust traps, releasing particles with every passing vehicle. A fleet of machines repairs cracks and potholes, each broken surface another source of dust. Scientists map the city’s dust hot spots, measuring exactly where particles settle.

This isn’t a small operation. It’s methodical, expensive, and runs day and night. And now, a single metro project threatens to undo it all.

Behind these dust-control measures lies a key metric: PM10. Dust matters so much to Naik because dust is mostly PM10. As we discussed the city’s initiatives, he kept returning to PM10, so we asked directly: “Do you measure PM10 especially?”

No, he said. They measure everything. “But the Central Pollution Control Board has told us that PM10 is a focus point.”

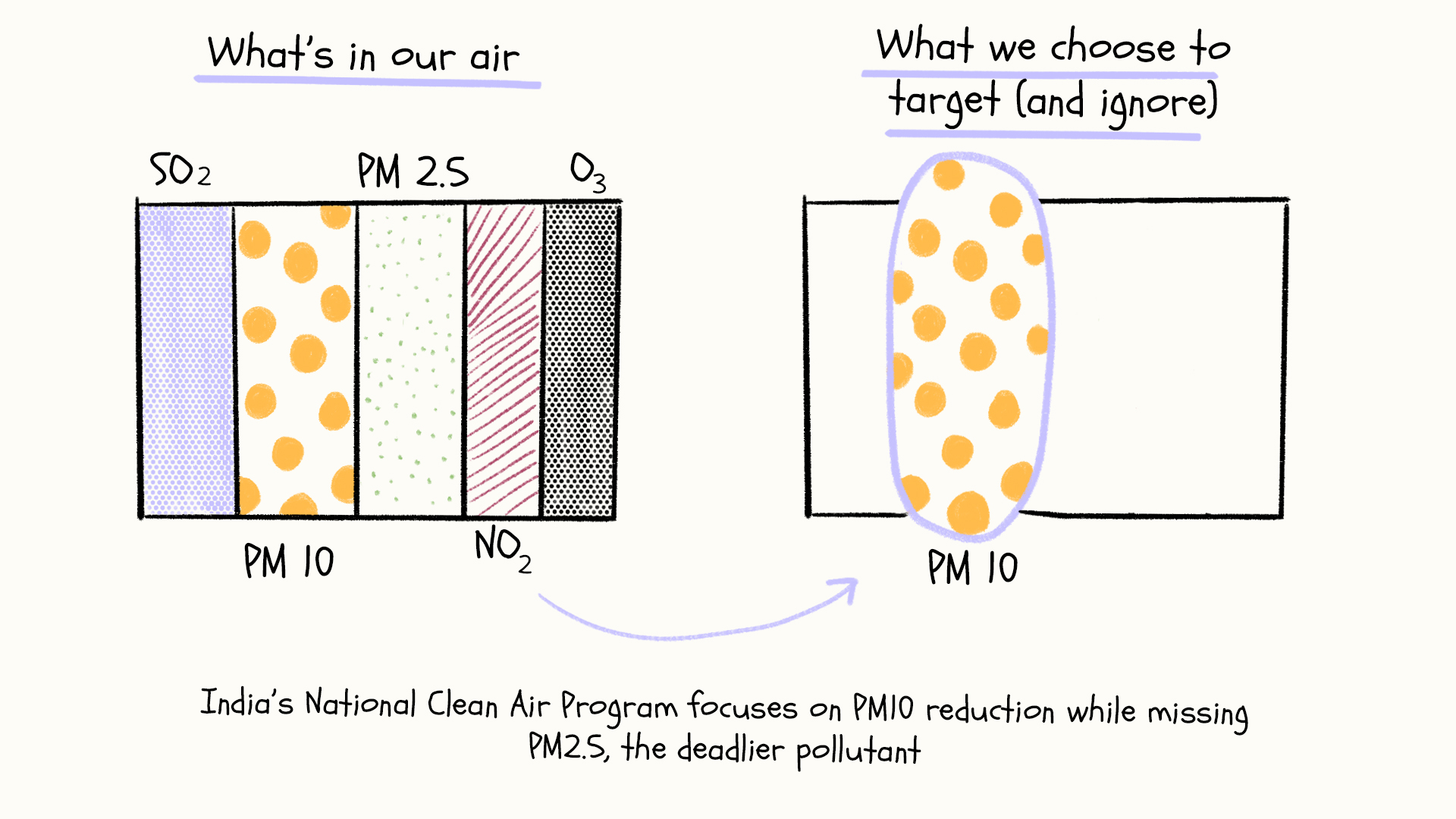

This was the first major change in NCAP’s policy in 2022. The government announced what it called a more “ambitious” target: not just a 20-30% reduction, but 40%.

The deadline was extended to 2026, and with this grand new number came a crucial shift: the pivot to PM10. Only focus on this one pollutant. PM2.5—the deadlier pollutant—vanished from the targets.

The change was presented as progress, citing “good performance” in cities like Varanasi, which apparently showed a 53% reduction in PM10 levels. But buried in the policy’s details was a critical mechanism: NCAP would now give additional weightage to dust from construction and roads.

This created a powerful incentive structure that shapes how cities fight pollution.

A quick glance at Clean Air Action plans (all available here) across cities will make you lose count of proposed solutions—it seems everything that can possibly be done is being planned and acted upon.

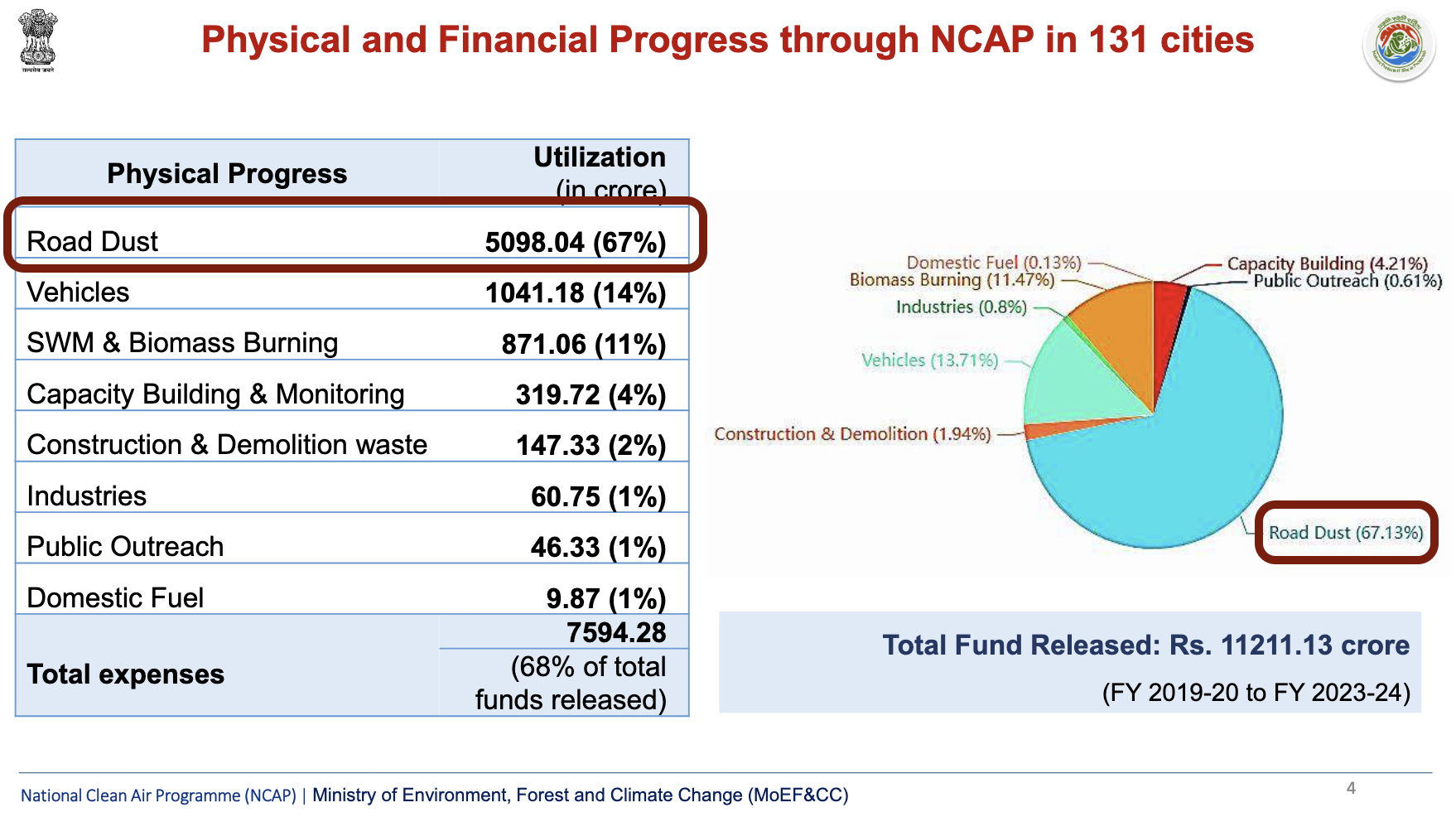

But follow the money, and you see the real priorities. As of September 2024, as per government data, ~₹5,100 crores of the total ~₹7,600 crores of NCAP funding utilised so far went in controlling road dust. (The Center for Science and Environment had highlighted this in July 2024.)

Just look at what this means. For every hundred rupees spent from central government coffers in its fight against pollution, 67 is going to mitigate dust. Cities are literally being paid to focus on the more visible, but less lethal threat.

To understand why this matters—why a seemingly technical shift in measurements has profound consequences for public health—you need to understand what we’re actually measuring, and what we’re choosing to ignore.

Air pollution isn’t one thing. It’s gases—like ozone and nitrogen dioxide—and particles of different sizes. The tiniest particles are our deadliest enemy.

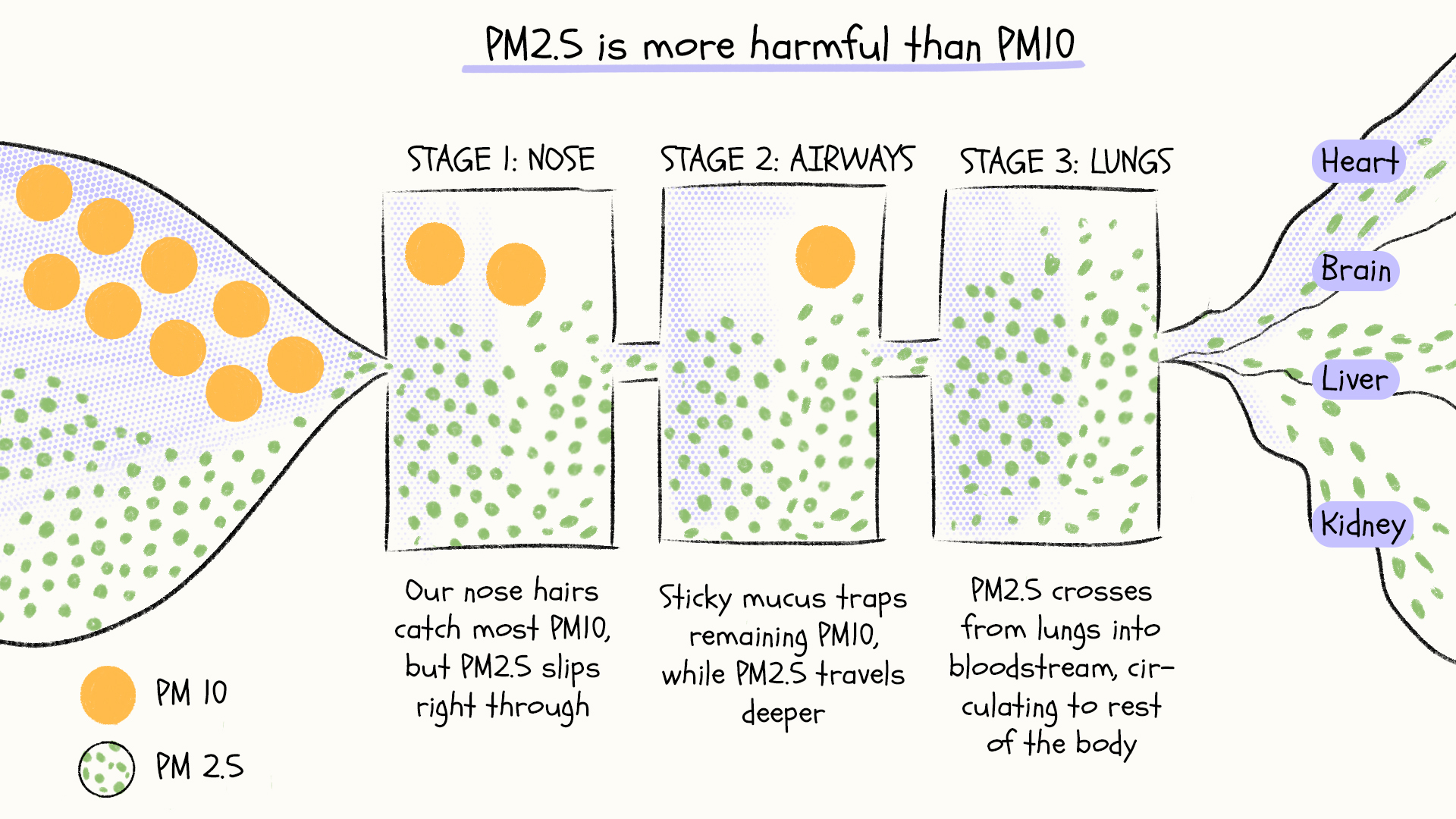

These particles—called particulate matter or PM—are measured in two sizes. PM10 particles are up to 10 micrometres wide. Some, like dust, you can see. Others you can’t. But your body has defences against them. They get caught in your nose, trapped in mucus, sneezed out. They’re harmful—they irritate your airways and cause breathing problems—but your body can fight them.

Then there’s PM2.5. These particles are so small that thirty could fit across the width of a human hair. And this is what makes them devastating. Too small to be caught by nose hairs or trapped by mucus, they slip past every defence your body has evolved. They reach the deepest parts of your lungs—tiny air sacs called alveoli where oxygen enters your blood.

From here, these particles enter your bloodstream, reaching your heart, brain, liver, and kidneys. Once inside, they keep your body in a constant state of stress and inflammation, damaging cells day after day, year after year. These are the same kinds of stresses that doctors warn about when they push you to exercise and eat healthy.

But here’s the cruel twist: Even if you follow every health rule—even if you exercise daily and eat the cleanest diet—you can’t escape these particles. In fact, when you’re out for your morning run, taking deep breaths, and pushing yourself to be healthier, you’re actually pulling more of these particles deeper into your lungs.

The numbers are staggering. The World Health Organization says anything above 5 micrograms per cubic meter is unsafe. India sets its standard at 40—already eight times higher. Delhi’s average is 131. And in those weeks when the media shows apocalyptic images of the capital city, the air carries 400, 500 micrograms of these particles.

The science of where these particles come from is clear. PM2.5 mainly comes from burning things—every time a vehicle runs, a factory operates, or a field burns, it releases these lethal particles. PM10, meanwhile, comes from mechanical processes like construction dust and unpaved roads.

Which makes what happened next almost absurd. “CPCB has explained to us,” Naik tells us, “that if you reduce PM10, then other pollutants will also get reduced, automatically.”

This isn’t just wrong—it’s backwards. Think about it: If you reduce larger particles like dust, how would that automatically reduce the tiny particles coming from vehicle exhaust or factory smoke?

“This is literally math,” explains Dr. Shahzad Gani, Assistant Professor at the Centre for Atmospheric Sciences at IIT Delhi. “If you reduce particles from 0 to 2.5 micrometres, you’ll naturally reduce the total particles from 0 to 10 micrometres—PM2.5 is part of PM10. But you can’t guarantee the reverse. You could be reducing only the larger particles while the deadlier small ones continue to rise.”

And yet, this weak claim now shapes how NCAP is asking cities to fight air pollution.

This is where the PM10 focus becomes more than just a technical choice—it’s an institutional escape route. Cities can control dust. They can’t control the system that produces pollution. So they chose to measure what they could manage, rather than manage what they needed to measure.

Because tackling the air pollution that kills requires something far more challenging. It means confronting four major sources: vehicles, industries, cooking and heating, and garbage burning. Each demands coordination across multiple levels of government, behavioural changes from millions of citizens, and substantial funding.

"We are actually cornering ourselves to not doing anything,” explains Sarath Guttikunda, director of Urban Emissions, and lead author of the comprehensive air quality review using satellite data we referred to earlier. “But on paper we’re showing that yes, we are doing something.”

The gap between paper and reality becomes clear in small moments. When we asked Naik about vehicles and industries, he seemed almost resigned. “When did you last get your PUC [Pollution Under Control] certificate updated?” he asked. When one of us admitted we hadn’t, he said with a knowing smile, “No one does!”

Even officials in other states acknowledge this reality. “We consider PM10 till date,” West Bengal’s pollution control board chairman Kalyan Rudra said in his critique at a conference in October 2024. “We don’t take into account PM2.5 which is more deadly.”

In short, NCAP was tweaked to measure success through easier parameters, fund the more visible solutions, and claim victory.

But there’s an even deeper problem with India’s air quality programme: We’re hardly looking at the air at all.

III. Looking Away

Back in Surat, we had a simple question for Naik: “How many air quality monitoring systems are you operating in Surat?”

“Ek. Ekajj. One, only one.”

But we had seen mentions of more in the documents. What happened to the 10 monitoring systems named in Surat’s action plan?

We quickly switched tabs to check their locations: "The one in Pandesara? Icchanath? BRC?"

That’s when we heard a long groan of recognition in his voice.

"Aaaah. Yes, those. Chaalta nathi. They don’t work."

"Did they all stop working?" we asked, confused because all of Surat’s baseline PM10 data until 2019—the data that shaped its entire action plan—came from these systems.

Naik corrected us. "No no, they work... yes... but these are manual monitors. Once or twice a month we get data from these."

What’s happening here is the difference between the two types of monitors. Manual monitoring stations are traditional measurement points where staff physically collect air samples twice a week. Think of it like taking a water sample from a lake—someone has to go there, collect the sample, and then analyse it in a laboratory days later.

The continuous monitors, in contrast, work like weather stations—measuring air quality every few minutes, all day and night, sending real-time data to a central system. These are the ones that matter to Naik.

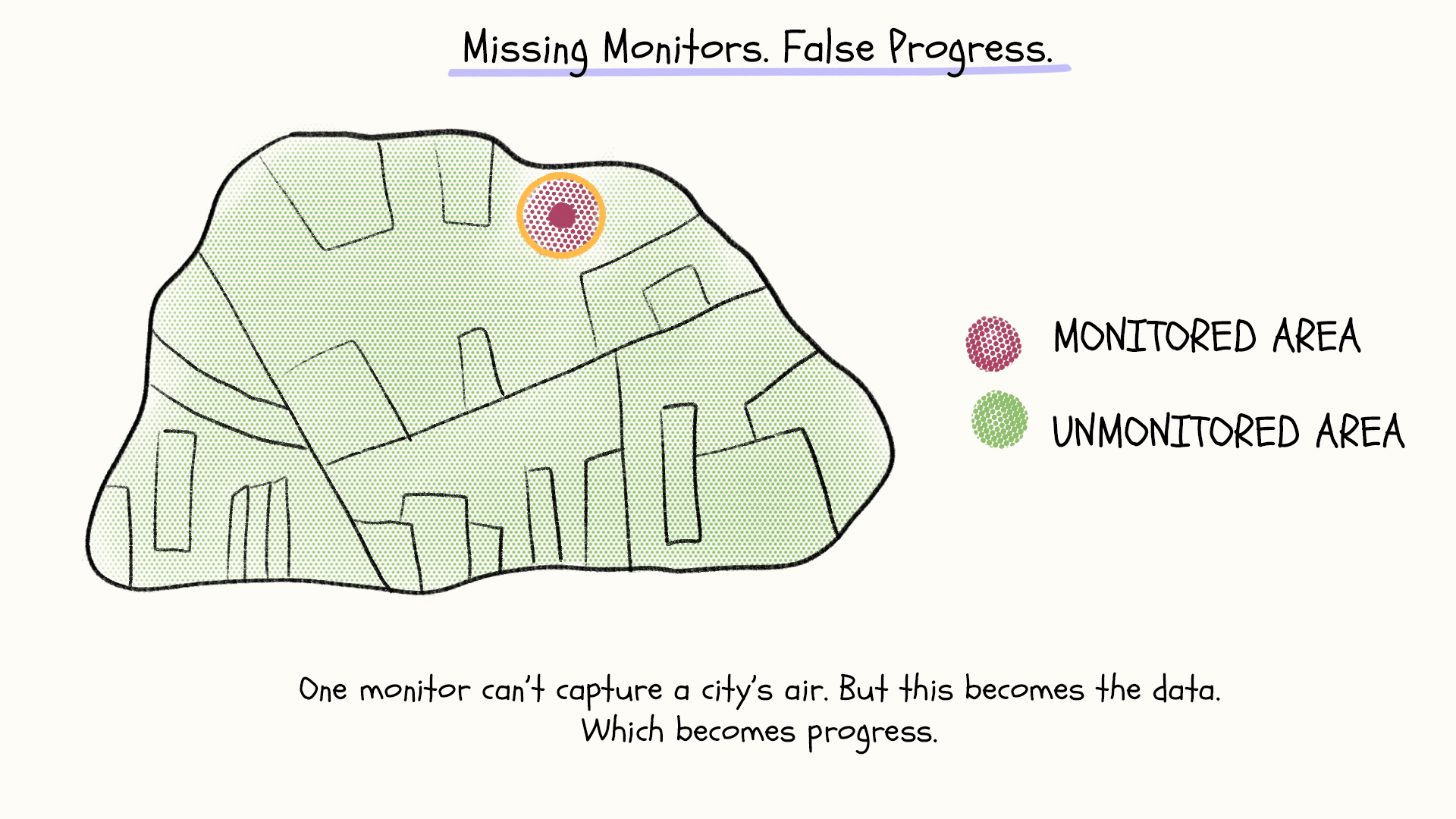

Think about what this means. The numbers which convince Delhi that Surat is doing well in the fight against pollution comes from a single continuous monitor. One data point for 8.3 million people—to determine the air quality of an entire industrial city. Which then shapes funding and shapes policy. Just one.

Guttikanda from Urban Emissions explained that a monitoring station can accurately represent air quality within a 2-kilometre radius in cities. Beyond that, buildings, trees, and varied pollution sources create too much variation.

“We mathematically dug down into what kind of numbers are coming out in each of these bulletins…both statistical analysis and CPCB’s own guidelines point to a minimum of four or five monitors. With less than that, we simply can’t tell a reliable story about a city’s air,” he explained. (Ideally, 25+ are needed.)

And here, Surat is not an exception. In December 2023, when Guttikanda did a review, only 15 of India’s 4000 cities had these minimum five monitors. Most don’t have a monitor. 215 out of 271 unique cities—80%—report data from a single monitor. It’s like trying to understand a city’s weather with one thermometer.

The progress isn’t zero. India has expanded its monitoring capacity impressively, growing three to four-fold since 2019.

But consider what it means for cities to claim successful pollution reduction based on measurements from a single monitor. These cities are announcing victory while seeing perhaps less than 5% of their air.

NCAP had a chance to fix this. Until it didn’t.

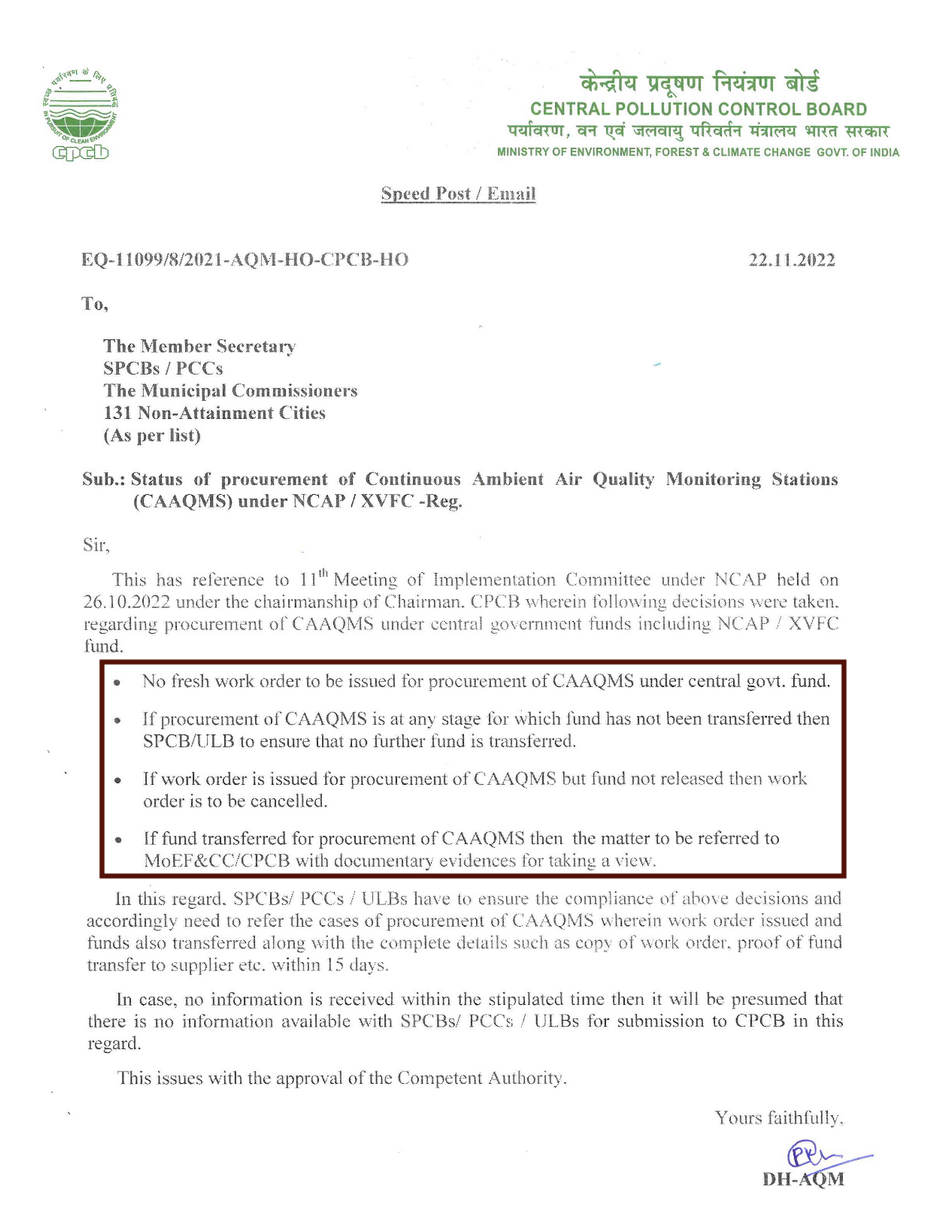

"Multiple were planned in the action plan, yes," Naik told us. “But it’s all been halted since we got a CPCB letter.”

This was in late 2022.

“What did it say?” we asked.

“Well, simple,” he explains. “We can’t use any funds to put any new monitors until further notice and new guidelines.”

Naik was not sure what these guidelines were or why they were linked to accessing funds already allocated to Surat.

Later, he sent us the letter—a terse one-pager on a CPCB letterhead, instructing all 131 NCAP cities that no work order should be processed for procuring any continuous air quality monitors from the central government fund. Even if orders were already placed, no funds were to be transferred. The work orders were to be cancelled.

The timing was odd. NCAP had emphasised the critical need for better monitoring—its own documents stress its importance.

The cost of seeing our air clearly isn’t small. Each high-quality continuous monitor costs about ₹1.5 crores, with annual maintenance adding another 10%. For a city of Surat’s size, a basic network of five monitors—spread across residential areas, industrial zones, and city centres—would cost ₹7.5 crores to install. These aren’t small numbers, but they seem modest for understanding what millions breathe.

“We want to focus on control of air pollution and not on procuring expensive equipment,” a senior official told the Hindustan Times. States could buy monitors with their own funds if they wanted. They would soon certify cheaper indigenous devices from the National Physical Laboratory.

It’s been more than two years—and CPCB hasn’t sent new guidelines. At least Naik in Surat hasn’t received any. The city continues to count its numbers from just one monitor.

Limitations like these are excused away as capacity and resource problems. That’s understandable. You can’t always have perfect data.

But this isn’t about perfect versus imperfect data. It’s about designing a system that generates just enough numbers to claim success, but not enough to reveal failure. A system that produces data too sparse to challenge the narrative, too limited to demand real change.

IV. Seeing Truth

Make no mistake. Many other local efforts are happening at the state and city levels. NCAP’s promise was to bring everyone together—to fight this together, sustainably. Air Pollution is one of the greatest ongoing public health crises of our time, and it deserves this large-scale coordination.

And look, this is a genuinely hard problem. NCAP’s original documents acknowledged this honestly. Cleaning India’s air would take decades of sustained, systematic work. The challenge is immense, urgent, and defies quick fixes.

Which is what makes this architecture of selective measurement so troubling.

This isn’t just policy failure—this is naked power. Each number we choose to collect, each measurement we decide to skip, shapes what we can see and therefore what we can solve. This is the true power of measurement—not just to describe reality but to define what counts as real.

In 1854, when cholera devastated London, John Snow did more than count the dead—he mapped each case, interviewed residents, and tracked water sources. He measured systematically, following evidence that challenged the conventional wisdom of his time. He built a system to see patterns others had missed, and in doing so, revealed the truth about how the disease spread.

Today, we see something different: a measurement system of convenience, a system where success exists on paper while the air tells another story. It’s about how a modern state chooses to see—or not see—the slow violence it allows against its citizens.

Until the seeing is fixed, we do have another way. Breathe.

All illustrations by Nayanika Chatterjee.

For feedback and comments, write to the editor at samarth@theplankmag.com