In October last year, police in Maharashtra’s Yavatmal district uncovered what desperate farmers had hidden in plain sight: twenty acres of illegal cannabis flourishing among cotton fields.

Six farmers from Ghonsara and Bargwadi villages were arrested. Authorities seized about a dozen quintals of cannabis—crops worth approximately ₹30 lakh.

For Yavatmal, long known as the ‘farmer suicide capital’ of India1, this discovery revealed the roots of a darker malaise. In this region, where farmers routinely swallow pesticides to escape mounting debts, cannabis—the plant notorious for producing the psychoactive drug marijuana—promises returns up to 20 times higher than cotton’s peak prices. It’s a dangerous gamble many are willing to risk in the face of economic desperation.

This gamble reflects a deeper crisis in Indian agriculture. Three years earlier and hundreds of kilometres away in Odisha’s Malkangiri district, when police destroyed 250 acres of cannabis plantations, over a thousand tribals protested with an unexpected demand. They’d switch to legal crops, but only after the government guarantees minimum support prices for turmeric, black gram and finger millets.

The message of these farmers was clear: legality meant little when survival was at stake.

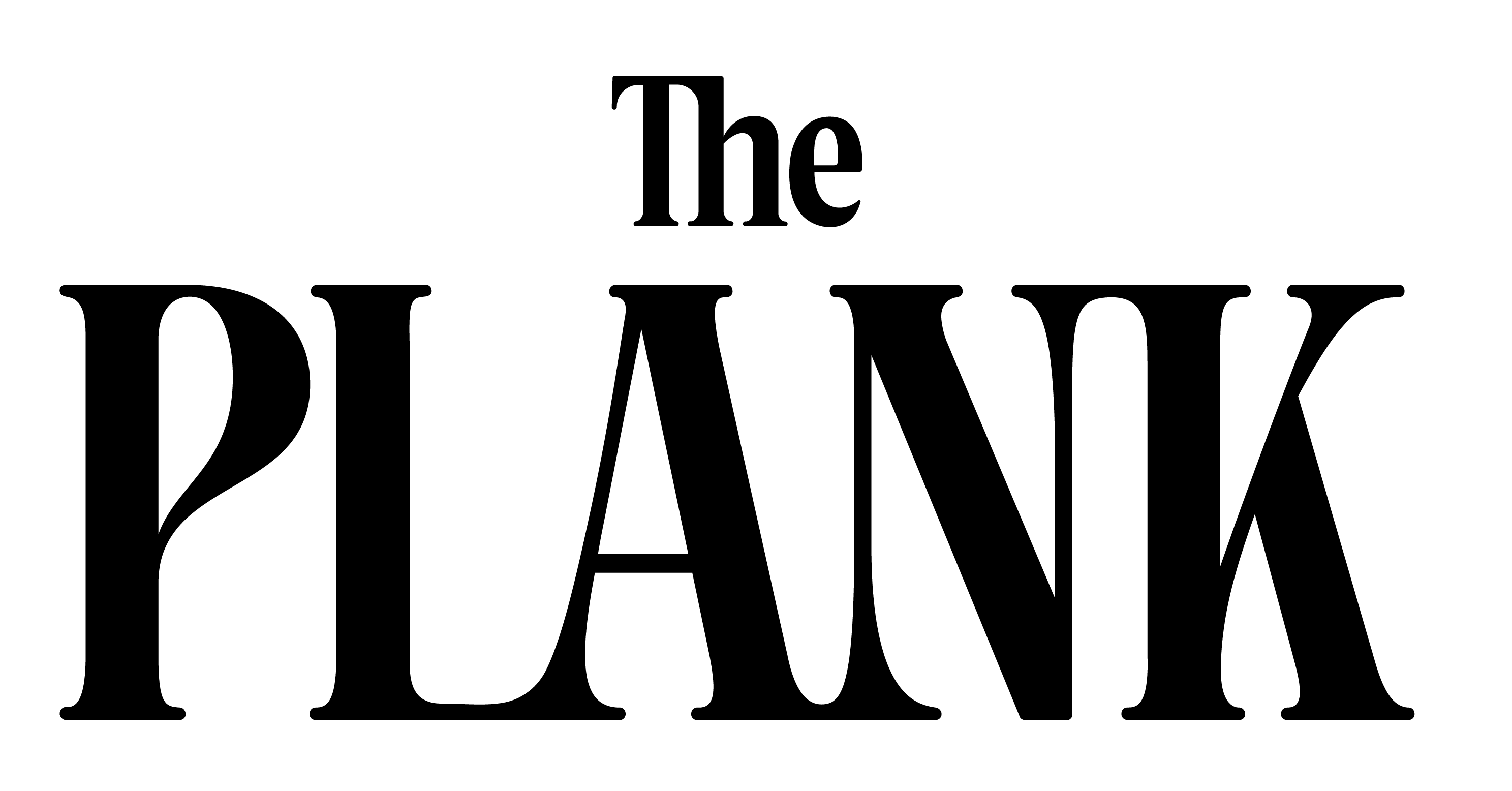

Despite its infamous reputation, cannabis is much more than just a source of an illicit, mind-altering drug. Its industrial variant hemp comes from the same species1 but contains minimal intoxicating compounds, and can be transformed into everything from textiles to construction materials.

China leads the global hemp industry, with just two provinces3 producing 50-70 per cent of the world’s hemp fibre. In Canada, where both hemp and medical cannabis are legal, the industry has revolutionised the economy, contributing roughly $43.5 billion to the country’s gross domestic product (GDP).

For farmers dreaming of better harvests, cannabis represents nature’s cruellest irony. The plant flourishes wild across the Indian landmass. Uttarakhand alone has more natural hemp than Canada, says Yash Kotak, one of the founders of the Bombay Hemp Company. According to former Narcotics Commissioner Romesh Bhattacharjee, cannabis possibly grows in nearly 60 per cent of India’s districts—and yet, its cultivation is largely forbidden as per the Narcotics Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (NDPS) Act.

This disconnect between abundance and restriction masks a historical relationship. For centuries, India maintained a pro-cannabis outlook, viewing the plant as both sacred medicine and a practical resource. It was cultivated for thousands of years, used for its medicinal, animal husbandry, and recreational properties, mentioned as a curative element in the Atharva Veda, and celebrated in popular tales from Hindu mythology.

Outside India, however, the plant gained a notorious reputation over the past century, often associated in the United States with racist tropes against minority communities and clubbed together with more dangerous substances like opium. At the 1961 UN Convention on Narcotic Drugs in New York, India stood firm against global pressure to restrict cannabis. The Indian delegation, armed with centuries of spiritual and medicinal tradition, secured a compromise to phase out non-medical use over the next 25 years.

As that deadline approached, India officially banned cannabis (alongside substances like cocaine and heroin) as part of the 1985 NDPS Act, marking a dramatic shift from traditional acceptance to strict prohibition.

What makes this reversal particularly complex is the plant’s very nature: different parts of cannabis serve a variety of radically different purposes. Its tough, fibrous stalks can be woven into rope or fabric. Its seeds, rich in protein and oils, can feed both humans and livestock. And controversially, its flowers (or ‘buds’) contain tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the compound infamous for its intoxicating potential.

This botanical complexity explains India’s contradictory approach to bhang, a paste made from cannabis seeds and leaves with deep roots in spiritual practices, particularly Shaivite Hinduism. While the NDPS Act criminalises ‘ganja’ (the plant’s flowering tops) and ‘charas’ (the resin obtained from the flower), India found an elegant regulatory solution: it simply excluded bhang from the legal definition of cannabis altogether — a distinction that recognises the substance’s spiritual sentiment. Today, government-approved bhang shops operate legally in pilgrimage towns across the country, from Varanasi to Pushkar, Jaisalmer to Mathura.

India now finds itself caught between prohibition and potential: state governments are testing the boundaries of what’s possible, farmers are risking prison for profit, and a new generation of entrepreneurs is rebranding ancient medicine for modern markets. Meanwhile, in research labs across the country, scientists race to create the perfect seed—one that satisfies both nature and bureaucracy.

It’s a precarious tightrope of science, agriculture, and law. For everyone involved—from desperate farmers in Yavatmal to Hemp entrepreneurs in Mumbai—the stakes couldn’t be higher. One misstep could turn a legal commercial enterprise into a crime ring.

In Uttarakhand’s Bageshwar district, 39-year-old Sanket Jain owns about 10 acres of land, most of which yields the usual suspects—wheat and rice. But one acre now stands apart, reserved for his entry into the newest agricultural frontier: industrial hemp.

Hemp’s appeal lies in its versatility and sustainability. It uses less water than cotton while producing more fibre per acre, making it an ideal textile alternative. Its seeds are emerging as a protein-rich superfood, while its rapid growth helps combat climate change—hemp plants breathe in four times more carbon dioxide than most trees; each acre can absorb 10 tonnes of atmospheric CO2.

In 2018, Uttarakhand became the first state to legalise cannabis cultivation exclusively for industrial hemp use. The economics seemed irresistible: early projections suggested farmers could earn ₹1 lakh annually per acre, with the state’s hemp textile industry alone expected to reach ₹240 crore.

Hemp’s global market potential added to the allure—projected to leap from $9.6 billion this year to nearly $30 billion by 2029, with uses ranging from textiles and paper to food, construction, biofuel, medicine, and more.

To Jain, the decision to apply for a licence was almost a no-brainer. After all, cannabis had flourished in these mountains for generations. The high altitude, alpine climate, and fertile soil of the Himalayas—from Pakistan’s Tirah Valley to Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh to Uttarakhand and the Northeast—had made the plant an integral part of mountain life. In these communities, cannabis has been woven into every aspect of life for generations. Jain remembers the snowy seasons of his childhood when fields lay depleted of vegetables. Only the hardy bhang crop survived the wintry frost, becoming a crucial source of sustenance.

“People prepare a chutney made of bhang,” he says, “mix it with lassoon (garlic) and eat it with chapati. In the coldest months of the year, this is the only option as a ‘vegetable’.”

The plant and its derivatives have served a variety of purposes: an ointment for bee stings, rope for shepherds’ footwear during long treks, seeds as seasonings in food, and even as an aphrodisiac. These uses persist to date, despite modern taboos that associate cannabis solely with narcotics, where words like ‘ganja’ or ‘charas’ are often uttered under one’s breath, evoking stereotyped images of glazed-eyed weed smokers and handcuffed smugglers and crowds of intoxicated men dancing around on Holi.

For farmers like Jain, however, the literal and cultural abundance of cannabis is not free of complications. The challenge lies in a single number: 0.3 per cent.

That’s the maximum amount of THC—the psychoactive compound that gives cannabis its controversial ‘high’—permitted in legal hemp. Jain estimates that the cannabis growing wild around his farm contains between 5 to 10 per cent THC, making it up to 30 times more potent than what the law allows.

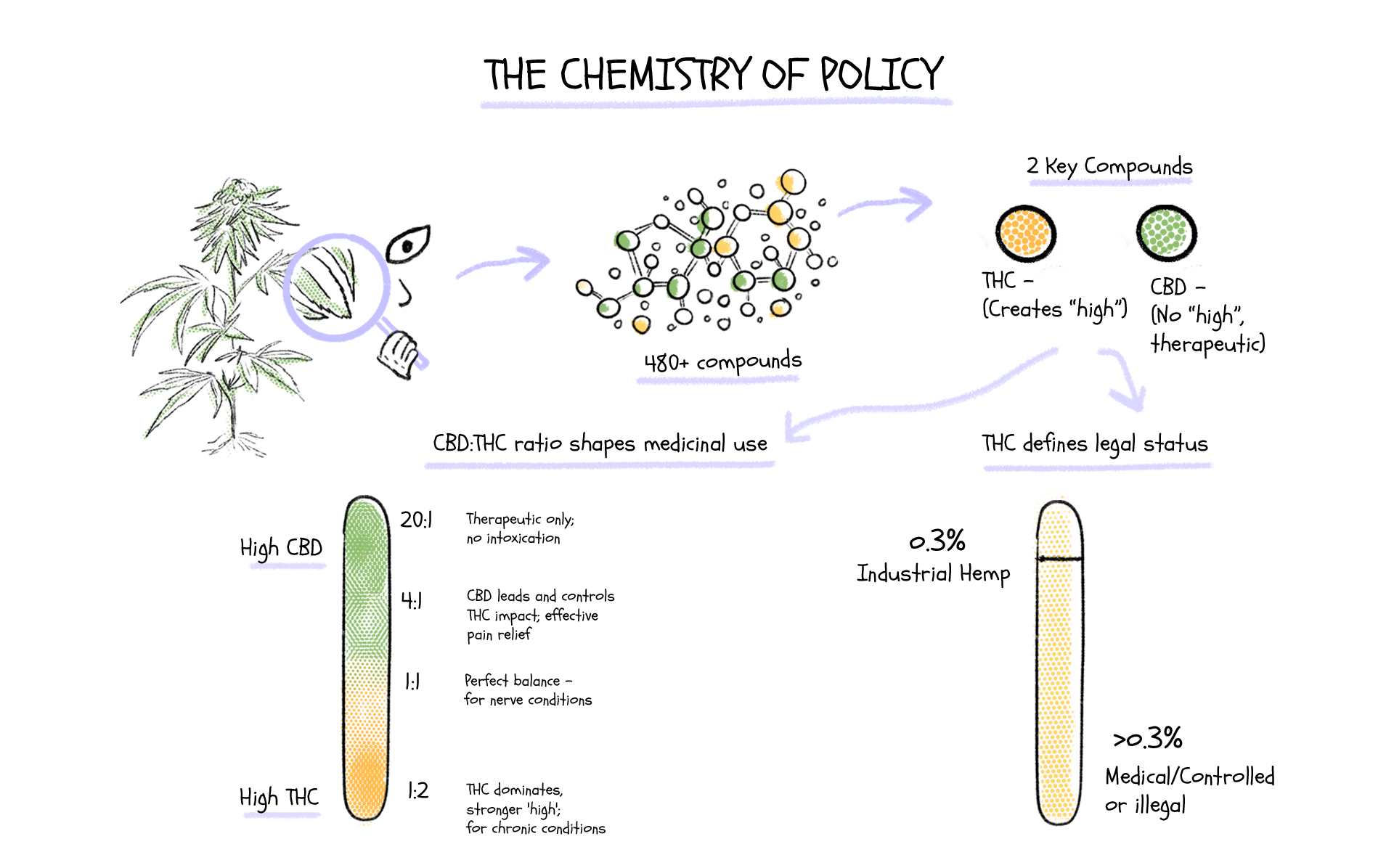

This seemingly precise threshold began as a botanist’s solution to a scientific puzzle: in the 1970s, Dr. Ernest Small was trying to determine whether cannabis was one species or several. He found two distinct groups in nature: northern plants with low THC used for fibre, and southern varieties with high THC used for drugs. Through extensive lab work later validated at the University of Mississippi, 0.3% THC content emerged as the chemical dividing line between these groups. What started as a scientific tool for classification would later shape policy worldwide.

Today, borrowed from U.S. agricultural standards, it creates an invisible line between legal hemp and illegal cannabis—one that is impossible to detect without laboratory testing.4

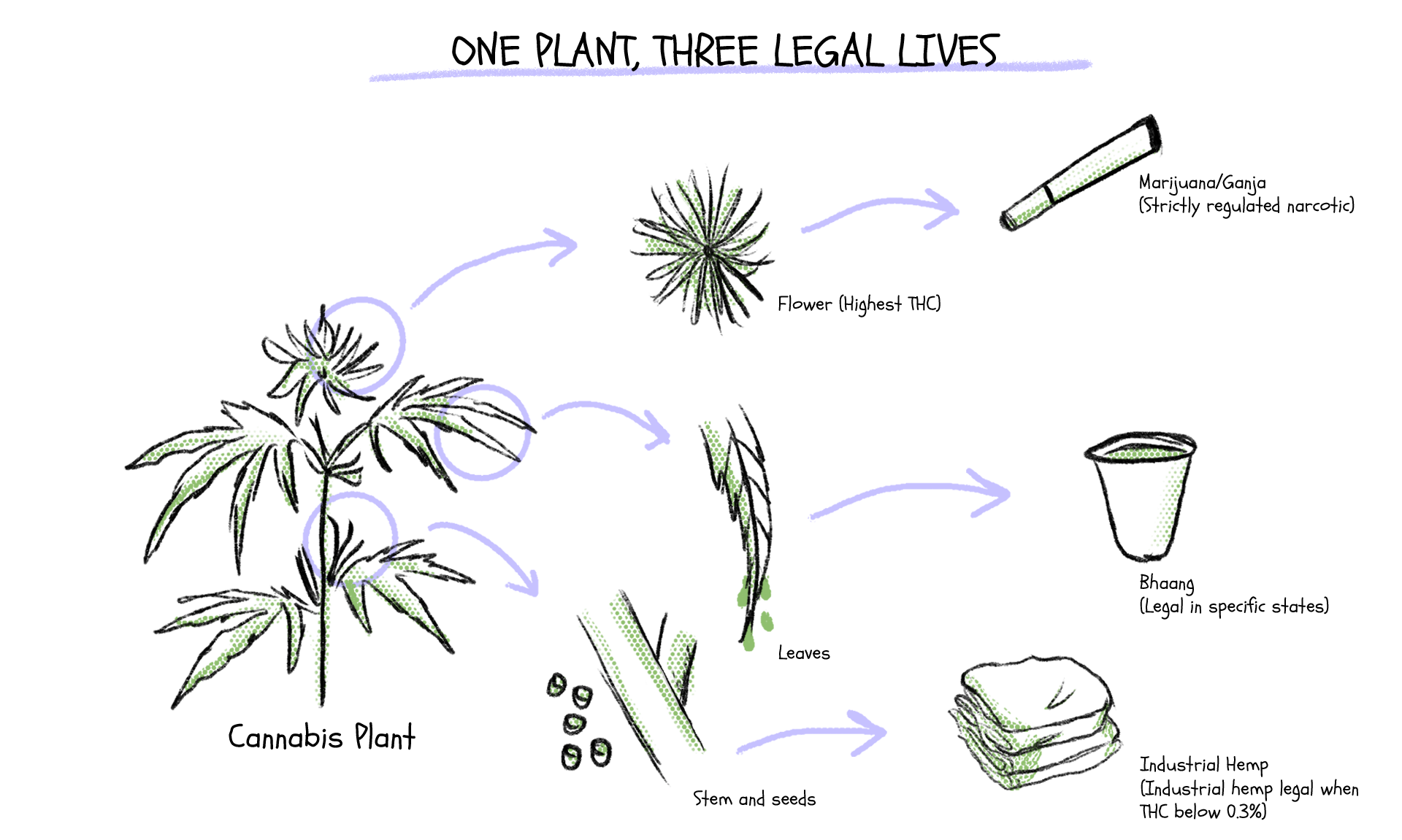

For Jain, this regulatory puzzle has meant endless bureaucratic hurdles. His licence application spent ten months ping-ponging between offices—from the district collectorate to the excise office, where he needed a No Objection Certificate. A letter was prepared and sent to six different departments, including the revenue office and the forest department. The letter would be passed through the hands of more patwaris, and be subject to more inspections.

The greatest resistance came from the state’s Excise Department itself, which seemed reluctant to encourage farmers to switch to hemp. The Excise Department in each Indian state enforces the state’s excise laws, most popularly, as the manufacture, distribution, and sale of liquor. Similarly, it is the responsibility of the same department in states like Uttarakhand to regulate and tax the nascent hemp industry.

“The first time I applied [for a licence], the officers themselves asked me, ‘Why do you want to do it? What if it’s abused?’” Jain recalls. “In the excise manual of our state, hemp has only two pages, out of a 280-something page book. There is so little attention given to us. So maybe they didn’t want another burden.”

For farmers like Jain—and the officials tasked with regulating them—there lies an invisible frustration: how does one police a plant whose legality lies not in its appearance, but in microscopic chemical differences?

The answer, it seems, lies not in more paperwork, but in science.

Two potential escape routes have emerged from this regulatory maze, each revealing its complications.

The first leads to a laboratory in Lucknow, where scientists are attempting to engineer nature into compliance with human laws. Since 2018, the National Botanical Research Institute (NBRI) has pursued an ambitious goal: creating the perfect low-THC plant that could transform illegal abundance into a legal opportunity. Under the leadership of then-director Saroj Barik, the institute obtained the first-ever licence in India to cultivate cannabis for research and development purposes. By the end of Barik’s tenure, his team had produced six different varieties of cannabis, each carefully calibrated to contain between 0.00 to 0.3 per cent THC.

But engineering compliant cannabis proved far more complex than anticipated. Each variety had to be artificially germinated, its chemical composition precisely controlled. Even more challenging was ensuring these plants stayed compliant—environmental stress, from drought to flooding, could cause THC levels to spike unexpectedly.

“We must be almost a hundred per cent sure the varieties will remain pure,” Barik told me over a call from his current post in Shillong. “One mix with different cannabis populations, and farmers could face criminal charges.”

It’s a delicate balance of genetics and chemistry—creating plants that will reliably produce low THC not just in one generation, but across multiple growing cycles, regardless of environmental conditions.

While the NBRI works on their long-term solution, farmers like Jain have tried a more immediate fix: importing seeds from abroad. The first seeds he planted came from Canada, carrying promises of compliance with global standards. But these imported solutions wilt in the face of local realities.

“It rains a lot in this region, sometimes for up to 96 hours straight. Only the indigenous variety will survive here,” Jain explains. His frustration runs deeper. “When we sow the seed in the soil, we say that the seed is the ‘blessing of the soil’. But the seed is the last part: after the flower is developed, and gets pollinated, then, the process of the seed is initiated. But how can the seed be obtained if the flower is banned in this country?”

For farmers pursuing either path—laboratory-bred or imported seeds—the burden of proof remains crushing. Once a year, Jain says that he must contact the Excise Department to collect samples from his farm for testing, which costs him ₹6000 each time. In more remote areas of Uttarakhand, farmers must bring samples across the wide breadth of the state to testing centres themselves.

“If the THC level is high, then the department may destroy the whole crop,” he explains. “So few want to take the risk.”

Barik points out that this entire framework rests on what he considers to be an arbitrary foundation. “There is no scientific validation that 0.4 per cent will make [the plant] an out-of-control psychotropic!” he says.

Ironically, the same chemical compound that makes cannabis illegal could also make it valuable. Barik’s research revealed that high-THC variants, properly regulated, could serve legitimate medical purposes, much like other controlled substances (like opioids) legally available in Indian pharmacies. This potential as a medicinal boon hasn’t gone unnoticed by India’s emerging cannabis entrepreneurs.

Often, a little rebranding is all one needs to secure some salvation.

The ancient Sanskrit word vijaya1—meaning victory—has become a bridge between India’s spiritual traditions and its emerging medical cannabis industry. Dozens of startups now offer cannabis-derived products under this carefully chosen label, highlighting the transformation of cannabis from contraband to cure.

When Sukkrit Goel’s 78-year-old grandmother was diagnosed with mouth cancer two years ago, her doctors suggested an unexpected addition to her treatment: a tonic containing CBD (Cannabidiol) and THC, two key compounds from cannabis.

The science explains why: our body’s endocannabinoid system regulates everything from pain and inflammation to mood and memory. And different compounds in cannabis interact with these receptors distinctly. THC—the same compound that creates legal complications for hemp farmers—targets pain and nausea, while CBD reduces inflammation and anxiety without intoxicating effects.

This connection between a substance’s psychoactive properties and its therapeutic potential isn’t unique to cannabis. Many powerful medicines, from morphine to anaesthetics, affect both body and mind. It’s often the same molecular pathways that allow a compound to alter consciousness that also enable it to intercept pain signals or reduce inflammation.

Several countries have recognised the medical uses of marijuana. In places where it’s legal, patients can be prescribed medical marijuana to ease the pain of chemotherapy procedures, severe nausea, muscle spasms, seizures, glaucoma, and more. One of the landmark medical cases was that of Charlotte Figi, an American girl with Dravet syndrome who suffered frequent, hours-long epileptic seizures from the time she was just three months old.

After failing to ease her pain from prescribed drugs like barbiturates, benzodiazepines, and radical diet control, Figi’s parents finally turned to medical marijuana in the form of CBD oil. The results were “stunning”, as the seizures eased immediately. Her story became a turning point that helped reshape U.S. cannabis laws.

Despite the positive momentum of the healing properties of cannabis-related compounds, Goel’s doctors in India hesitated to prescribe his grandmother with CBD, given her advanced age, and the risk of adverse side effects. Goel eventually went through with administering the CBD. However, worried about the associated taboos, he didn’t tell her that there was cannabis in her medicine.

The treatment worked. Today, at 80, she’s alive and healthy again. “She felt good,” Goel says, “and it helped her a lot.”

This experience led Goel to found Cannazo India, which gained national attention on the reality show Shark Tank India. But even as a businessman, he maintains the careful distance from cannabis that helped his grandmother accept treatment. His products carry the name vijaya rather than cannabis, and their packaging avoids any hint of the controversial plant.

“We treat it as medicine,” he says. “Otherwise customers might only see it as an intoxicant.”

This duality plays out at the highest levels of Indian governance. The Ministry of AYUSH embraces cannabis-derived products as part of India’s traditional pharmacopoeia, alongside herbs like ashwagandha and neem. But the Excise Department views the same plant with deep suspicion, as more of a nasha (intoxicant) than a dawai (medicine). Companies like Cannazo must carefully navigate between these competing visions.

The challenge isn’t unique to India. The U.S. National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) has documented serious risks with recreational marijuana use, including anxiety, fear, hallucinations, elevated heart rates, and medical emergencies from high-THC products.

America’s opioid crisis offers a cautionary tale: in the 1990s, pharmaceutical companies promoted prescription opioids as safe painkillers, leading to devastating addiction rates. A few years ago, the World Health Organization reported that, out of the 600,000 deaths in 2019 attributed to drug use, close to 80 per cent were related to opioids.

While cannabis carries far lower risks than opioids, the fundamental question remains: is it a nasha, then, or a dawai? The slippery definitions of cannabis often depend upon the eyes of the beholder or the unsteady definitions offered by various nation-states around the world.

On a hot summer day in Telangana’s Bhuvanagiri town, members of the Railway Police and a drug disposal committee dragged out dozens of sacks filled with seized cannabis to burn in a tall, raging, black metal furnace. A video of this grand cremation ceremony shows a group of policemen, wearing facemasks in front of the smoky fire, gleefully throwing the sacks inside the furnace, like a game of cornhole. By the end, the fire seethed with a loud, frightening flare, the sound of destruction. Over 1,500 kilograms of cannabis—worth approximately ₹4 crore—was turned to ash.

This scene repeats every June 26, which is observed as the International Day against Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking. In 2022, Karnataka police burnt ₹25.6 crore worth of narcotics; more went up in flames in Haryana’s Panchkula and Ambala. Beyond India’s borders—from Laos and Iran to Cambodia, Liberia, and Myanmar—authorities light similar bonfires with ceremonial precision, turning this summer afternoon a little hotter every year.

These ritual burnings—performed with almost religious fervour, a Holika-Dahan of drug destruction—stem from a legal framework that makes no distinction between cannabis and harder narcotics like heroin and cocaine.

In Raipur, while virtually inaugurating the Narcotics Control Bureau’s (NCB) Zonal Unit Office in August 2024, the Union Home Minister Amit Shah expressed the government’s desire to push for India to be “drug-free” by 2047, the centenary of the country’s Independence.

The numbers he presented were stark: compared to the previous decade, the government is now alleging a 257% increase in drug seizures, with authorities confiscating narcotics worth ₹22,000 crore between 2014 and 2024.

“Illicit trafficking of narcotics in India severely impairs national security,” Shah said, outlining plans to establish NCB offices in every state. “Money earned from illicit drug trade promotes terrorism and left-wing extremism and weakens the country’s economy. Drugs not only ruin the country’s young generation but also weaken the country’s security.”

The Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment reports that 3.1 crore Indians use cannabis in some form, with 72 lakh suffering from cannabis-related problems. Drug dependency ripples beyond individuals, destabilising families and trapping communities in cycles of poverty and crime.

But placing cannabis in the same category as harder drugs and treating all substances with equal severity could be counterproductive, driving otherwise legal agricultural activity underground. Under the NDPS laws, farmers and couriers face prosecution and arrest, regardless of scale or intent.

Between 2020 and 2023, enforcement authorities seized close to 24 lakh kilograms of dry ganja from smugglers operating around India. For comparison, Jain’s one acre of land dedicated to cannabis produces just around 500 kgs of the same.

The true cost of this regulatory paralysis can’t possibly be measured in kilograms or crores. It’s counted in the thousands who face incarceration, the farmers who lose opportunities for legitimate livelihood, and the patients who struggle to access medicine—all while cannabis continues to grow freely across much of India’s landscape, mocking these human attempts at control.

Even as these acts of destruction continue, change flickers on the horizon. A few months after I spoke to Barik, his vision for a more liberalised medicinal cannabis policy took an important step forward: Himachal Pradesh officially proposed legislation to legalise cannabis cultivation in September 2024.

Beyond just industrial hemp, the state aims to go further—proposing licences for farmers to cultivate and collect the plant’s higher-THC components for medicine and scientific research. With projected annual revenue of ₹2,000 crore, Himachal’s model could become a template for other states to follow.

For all the complexity of cannabis policy—from laboratory breeding to medical research and drug enforcement—the reality for farmers like Jain often comes down to more mundane frustrations.

A few days after our conversation, Jain had planned to travel to Gujarat, and he complained of another thoroughly Indian inconvenience that he faced: reserving railway tickets. “I booked a ticket from New Delhi to Khodhiyar 90 days before the date, and was still put on the waiting list. And after 90 days, the ticket still didn’t get confirmed. It’s Waiting List, everywhere. How can the common man travel?”

The liberalisation of India’s hemp policy, he says, “moves.... like the passenger railway. Slowly, like a maalgari. Some places have no track at all. And we don’t know when we will get the green signal.”

- In June 2024, Yavatmal’s neighbouring district, Amravati, recorded more farmer suicides than Yavatmal—and is now dubbed the ‘new farmer suicide capital’. ↑

- Industrial hemp comes from the same species of cannabis but is traditionally derived from a specific subspecies, Cannabis sativa, which grows taller and produces more fibre compared to another subspecies, Cannabis indica. ↑

- In China, only two provinces—Heilongjiang and Yunnan—are legally allowed to grow hemp, although it is cultivated illegally in others. These two provinces officially account for the majority of the world’s hemp production. ↑

- According to the Department of Revenue, the ’production, manufacture, possession, sale, purchase, transport, import inter-state, export inter-state, or use of narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances’ carries a penalty of up to six months’ imprisonment, a ₹10,000 fine, or both for what is defined as a ’small quantity.’ Larger ’commercial quantities’—defined as 1 kg for charas and 20 kg for ganja—can result in 10 to 20 years in prison and a fine of ₹1–2 lakh. ↑

- Vijaya was the term used to refer to cannabis in ancient Hindu texts, including the Atharva Veda. Apocryphally, this term connects cannabis with amritha, a golden nectar said to have been created during the churning of the ocean, symbolising the victory of the gods over demons in Hindu mythology. Some stories even claim that the first drop of amritha fell to the earth and sprouted the cannabis plant. ↑