In April 2024, as crew members of Bade Miyan Chote Miyan went public about their unpaid dues, a focus puller named CH Ravi Kumar made frantic calls from his hospital bed. Bedridden for eight months, he had exhausted his insurance, borrowed money for medical bills, and was still owed around ₹1.5 lakh for his work on the film.

While he and countless others—from spot boys earning ₹1,000 a day to equipment suppliers owed lakhs—pleaded for their payments, the production office behind the ₹350 crore spectacle was eerily quiet, trucks parked behind its towering movie poster as staff hurriedly packed up and left.

The film had everything that was supposed to guarantee success: two bankable stars in Akshay Kumar and Tiger Shroff, high-octane action sequences shot across exotic locations, and a proven commercial formula. Kumar alone was reportedly paid ₹100 crore—more than the film’s entire theatrical earnings of around ₹80 crore.

The math was catastrophic: a ₹250 crore loss in a single weekend, making it what one trade analyst called ‘the worst week in Hindi cinema’s history.’

In the aftermath, the industry scrambled for explanations: The trailer didn’t work. The music failed to connect. The production house lacked experience with spectacles of this scale. Some blamed the dated action, comparing it to forgotten Hollywood films from a decade ago. Others pointed to Akshay Kumar’s declining box office pull—this was his eighth flop in ten releases. A few wondered if audiences had simply grown tired of tech-heavy action movies lacking emotional core.

All of these explanations miss something fundamental. Each movie represents both a creative leap of faith and a multi-crore financial investment. This dual nature creates a central tension: how do you respond to uncertainty when nobody really knows what works?

For years, the industry believed it had the answer: stars, spectacle, scale. The formula was meant to reduce uncertainty, to ensure audiences would turn up. Instead, it has made failure more expensive than ever.

This is a story about a system straining under its own contradictions—what happens when an industry tries to eliminate risk instead of learning to live with it.

Movies have two sources of capital that shape everything. Audiences decide what they’ll pay to watch. Producers, watching these signals, decide what they’ll fund.

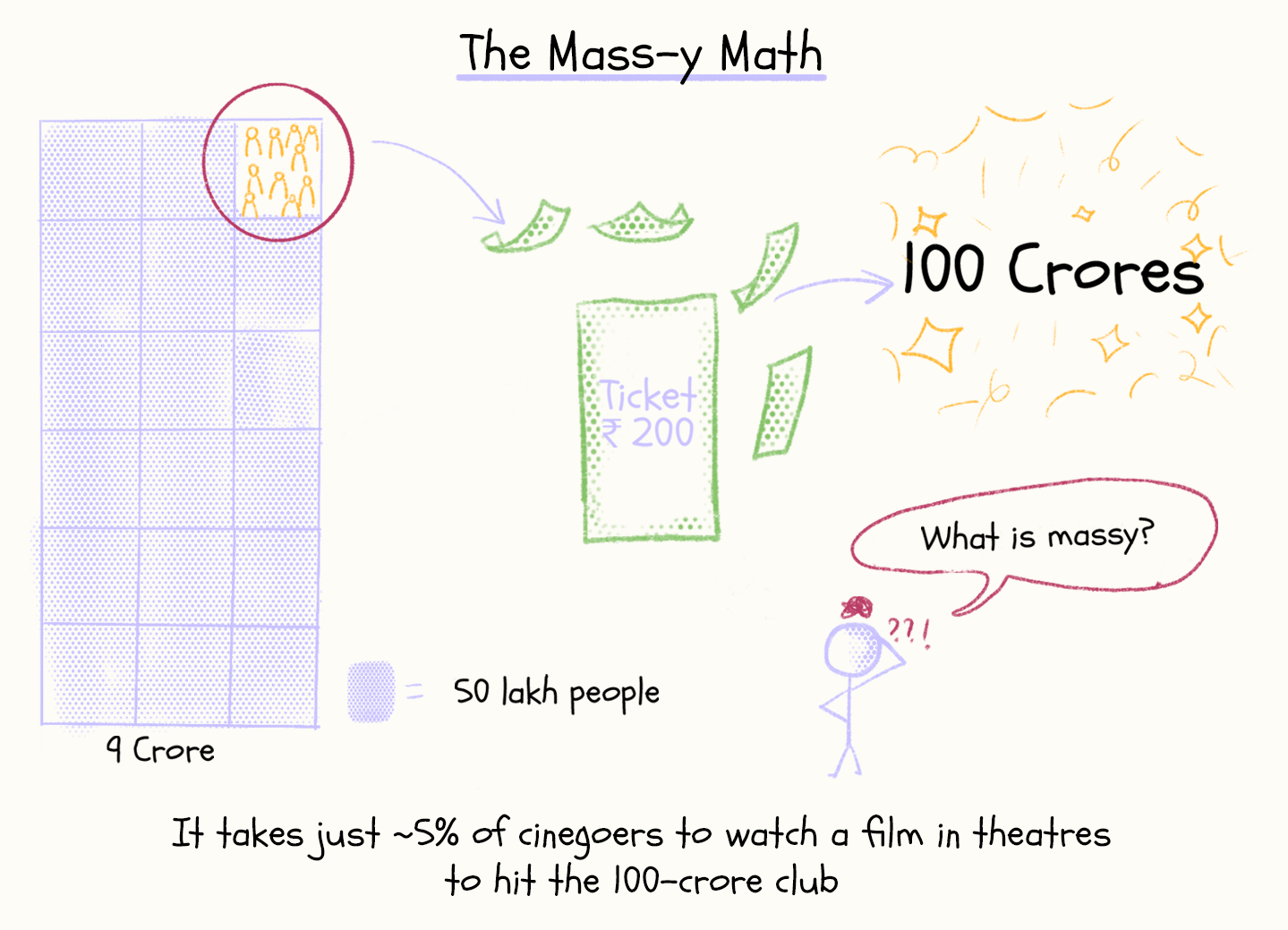

The audience remains massive: we are talking 9.2 crore theatre-going people who watched at least one Hindi film in 2023.

What has changed is what it costs: going to the movies is becoming increasingly expensive. A Hindi movie ticket now averages ₹203—nearly double what Telugu (₹110) or Tamil audiences (₹95) pay.

Add in the soaring cost of popcorn and cola—now ₹132 per person, up from ₹72, according to PVR data—and a family of four might spend over ₹1,500 for one movie outing.

At these prices, people are becoming selective. The fall in attendance is stark: from 34 crore tickets in 2019 to 23 crore in 2024. Empty seats multiply: PVR’s theatre occupancy has dropped from 34.3% to 25.6% over the past four years.

The most significant shift is in how often people show up. Hindi film audiences now catch just three movies a year in theatres. Compare that to nine films for Telugu audiences.

“The habit of watching is far more in the South than in Hindi,” said Shailesh Kapoor, CEO of Ormax Media which produced these numbers. “Watching three Hindi films a year means going once every four months—that’s not a habit, it’s event viewing, like going for Diwali. Compare that to eight or nine films a year in the south, where people are going every month or once in five, six weeks. That’s a habit.”

Producers read these signals: if audiences treat movies as events, make them event-worthy. If you only get three shots at capturing them each year, make each shot spectacular.

“It’s a hard time for storytellers because somehow the perception is that the audience only wants to step out of their homes to watch big budget tent-pole films,” Ishita Moitra, one of the key writers behind Rocky Aur Rani Ki Prem Kahaani, told me.

To understand what’s at stake, consider how Hindi cinema’s economics work.

Broadly speaking, the industry operates in three distinct segments: tentpole films (budgets above ₹80 crore), mid-budget movies (₹30-80 crore), and small films (below ₹30 crore). Each tier traditionally served different audiences, stories, and commercial goals.

What does it take to make it to the coveted 100-crore club?

At an average ticket price of ₹200 for Hindi movies, about 50 lakh people need to show up at the theatres. That’s 5% of its core audience. That was the benchmark for success.

Look at what’s happening now. Take Kalki 2898 AD, with its ₹500 crore budget. It’s what the industry calls a ’pan-Indian’ film, reaching beyond Hindi cinema’s 9.2 crore base to target India’s entire theatrical audience of 15.7 crore. At an average India ticket price of ₹130, to earn say ₹800 crore—the kind of return such budgets demand—it needs to sell five to six crore tickets.

That’s almost one in every three moviegoers in India.

Beyond mere inflation, this represents a fundamental reimagining of what a "big" movie means. And it hasn’t just made big movies expensive—it’s made all moviemaking more expensive.

“If I go back just six years, the cost I made Mukkabaz in, today I have to spend five times the money in six years for the same movie to make it exactly the same way,” filmmaker Anurag Kashyap said in a recent interview with THR India. “It is now difficult for me to go out and experiment because it comes at a cost.”

As I interviewed people across the industry, one factor kept emerging as the key driver: star salaries and their cascading costs.

"I am so fed up," Karan Johar said at Film Companion’s Producers Adda in 2021. "I have seen actors’ prices rise through the worst period of cinema, for no reason. There was an X amount; three months later, it is here, three months later it is there. But, why? They have not had a release, their last release was a failure, their films have not taken off and yet they are just going on."

Three years later, nothing had changed. In another roundtable with THR India in 2024, Johar gave an example that reveals the absurdity of Bollywood’s star-centric economics.

He produced a small high-concept action film, Kill. “Every star asked me for the same money that the budget was for. I would say, how could I pay you? When the budget is 40 crore, you asked me for 40 crore? Are you guaranteeing that the film will do 120 crore?”

The demands have become bizarre. One star insisted on having his driver transport his personal car to every city he flew to for shoots. Another demanded multiple hotel suites during outdoor shoots—one to stay, one for staff, a third just for getting ready. During a UK schedule, a star demanded his entire family be accommodated throughout the shoot in a villa. When they arrived, the production received an angry call—the mansion was perfect, but where was the tea pot?

The roots of this escalation trace back to the pandemic, when streaming platforms started paying unprecedented sums. Stars who charged ₹5 crore for theatrical films were reportedly offered ₹15 crore for streaming projects. Those rates became the new normal, even as theatrical returns remained uncertain—and streaming funds have now dried up.

“OTT barged in during the COVID times…for one Rajinikanth film, one Vijay film, we’ll give 120 crore. You be like, we will make it,” Tamil film director Vetrimaaran said in the same THR India roundtable.

“Then the budgets became bigger, the salaries became bigger. And within a few months, they realised that it’s not sustainable for them. So the OTT platforms…are saying, ‘Okay, we can’t give that much.’ But the filmmakers have gotten used to making bigger films, and actors have gotten used to taking bigger salaries. What to do now?”

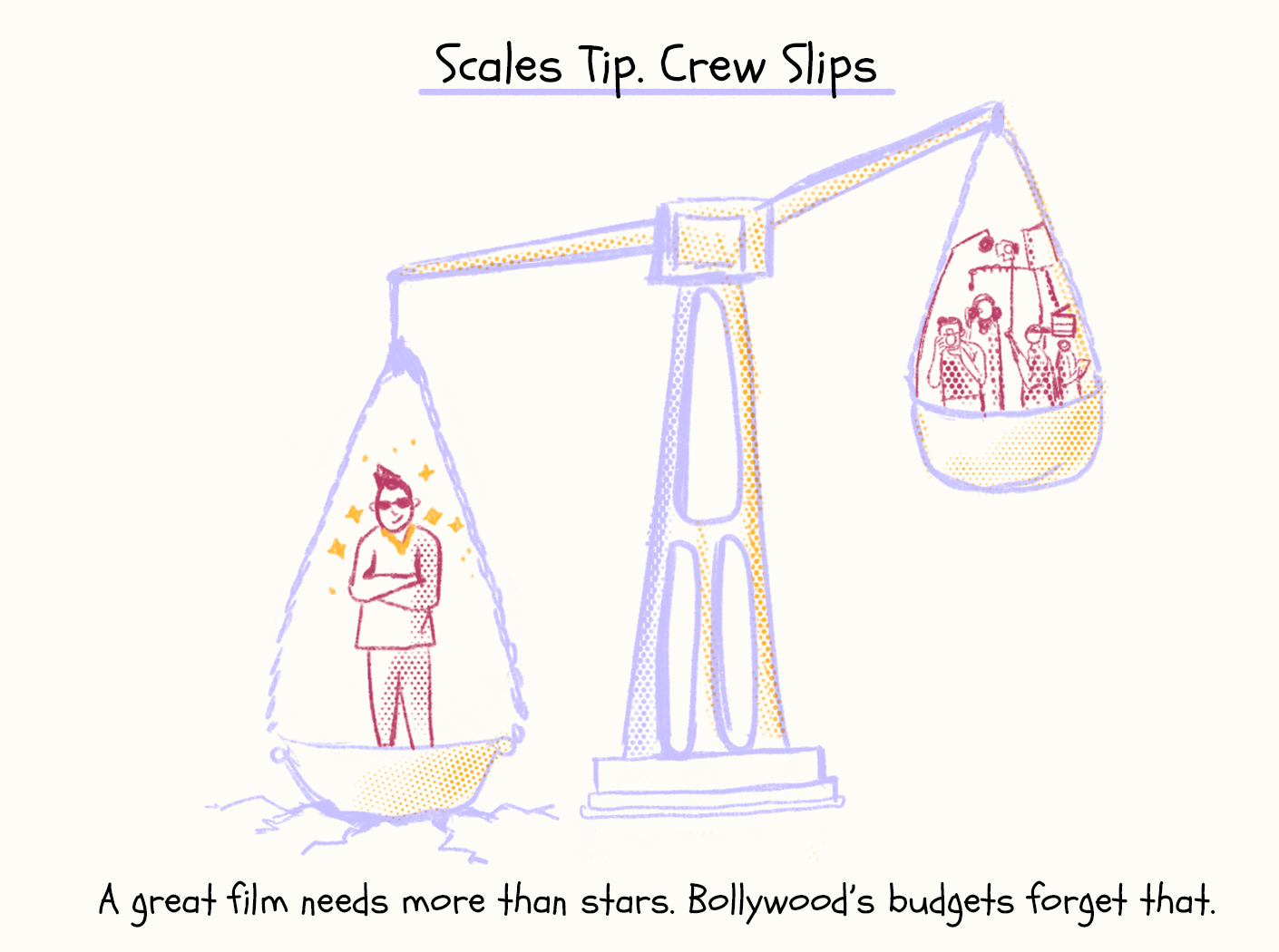

This creates a brutal accounting reality: when you spend most of your money on stars before shooting begins, something has to give.

The industry divides costs into two categories. Above-the-line (ATL) costs—stars, directors, key creative talent—get paid upfront. Below-the-line (BTL) costs—the countless technicians, crew members, and post-production talent who actually make the film—get paid during and after production.

When 70% of your budget is locked into ATL costs before a single frame is shot, the remaining 30% has to stretch across everything else. This creates a cascade of compromises.

Take editing. "An average editor is offered not more than 20 lakhs for a film. And that is also, like, on the higher side, half the time," says Antara Lahiri, who has edited projects like Delhi Crime and Call Me Bae. Meanwhile, stars command fees in the tens of crores.

But the issue runs deeper than just pay disparities. "Any art or craft—be it singing, dance, painting, or filmmaking—requires practice to improve," Lahiri explains. "You find different ways of using the software, or the camera, to evolve your language. When you pay for a skilled professional, you’re not just paying for the hours they put in—you’re paying for their experience."

Beyond questions of fairness, this reality shapes what kind of films can get made. As Lahiri points out, audiences aren’t watching raw footage; they’re watching the work of editors, cinematographers, and countless others who refine and construct a film’s story. When these craftspeople are replaced by cheaper alternatives, when every department is squeezed to accommodate ballooning star fees, the result isn’t just frustrated talent—it’s compromised storytelling.

The industry is well aware of this. But awareness hasn’t translated into meaningful change—yet. In a system built on the illusion of certainty, stars remain the closest thing to insurance—even as that insurance becomes ruinously expensive.

And the consequences go beyond individual films, reshaping Hindi cinema in two major ways.

First, the industry is becoming increasingly dependent on massive hits.

In 2023, four Hindi films—Jawan, Pathaan, Animal, and Gadar 2—each crossed ₹600 crore. They were lifelines. Jawan earned ₹760 crore on a ₹300 crore budget, Pathaan made ₹657.5 crore on ₹250 crore, and Animal brought in ₹915 crore on ₹100 crore.

This kind of concentration is unprecedented. In 2018 and 2019, the top 10 Hindi films accounted for about 50% of total box office earnings. In 2024, that share jumped to 70%—with just one film, the dubbed version of Pushpa 2, contributing to 20% of total Hindi box office collections.

The big are getting bigger—but something else is disappearing: the middle.

"What’s happening is that smaller films, even when they do well, can’t get beyond a certain business, while the bigger films continue to get bigger," Kapoor from Ormax said.

"The dependence is more on the top five or six films of the year. You’re going to be more and more reliant on blockbusters and festival releases. But in between, there are large gaps of two, three months when that kind of film may not come. You’re running at 10-15% occupancy. It creates a lopsidedness in the business model."

The vanishing middle represents more than numbers alone—it marks the disappearance of opportunity. These were the films that once made careers. Movies like Piku, Neerja, and Kapoor & Sons, made for between ₹10 and ₹40 crore told unique stories and created stars like Ayushmann Khurrana and Taapsee Pannu. They were spaces for experimentation, for new voices, for risks that could pay off without betting the farm.

"Some of my passion projects and stories that I hold very dear to my heart are waiting to be told," Moitra, the screenwriter, said. "Small and medium budget films are the bread and butter of the film industry. Just 4-5 big scale films a year that bring in theatrical revenue cannot sustain the entire workforce in the longer run."

This is the invisible crisis of Hindi cinema’s scale obsession. When the middle disappears, so does the training ground for talent, the space for fresh voices, the films that keep audiences coming back between blockbusters. The entire ecosystem that makes those blockbusters possible starts to erode.

And so, a self-reinforcing cycle begins. Fewer mid-budget films mean fewer reasons to visit theatres. Fewer theatrical visits mean greater pressure for each release to be an event. The cycle tightens: an industry built on the search for guarantees keeps making cinema-going less habitual and more exceptional.

It might seem almost paradoxical—perhaps even a bit disheartening—to scrutinise the business model when the real argument is to shift focus away from the numbers and back to storytelling.

The irony isn’t lost on me, especially after Hansal Mehta, brimming with frustration, told me during an early morning call, "It’s absurd to mistake cinematic merit for box office success. It’s a smokescreen for mediocrity, designed to perpetuate it."

This tension isn’t new. As Karan Johar recalls Yash Chopra saying: “A film doesn’t fail; a budget does.”

The crisis in Hindi cinema isn’t about making movies; it’s about making them at the right price. When budgets become detached from potential returns, when star costs spiral beyond reason, when each film must be an event to justify its economics, you get stuck in a trap—a mediocrity trap.

This is the fundamental contradiction at the heart of the industry today: in trying to eliminate uncertainty through star power and scale, Bollywood has made success even more uncertain.

What does this contradiction look like in practice? A revealing answer emerges by studying the financials of two production houses.

In October 2024, Johar’s Dharma Productions—the house that defined Bollywood glamour for decades—sold half its stake to Adar Poonawalla for ₹1,000 crore. The deal was about survival.

Around the same time, across town, Maddock Films was celebrating. Their latest release, Stree 2, had become 2024’s highest-grossing Hindi film, going beyond ₹700 crore.

Two studios, two very different stories—best understood through their numbers.

Maddock Films made ₹79.6 crore in profit in the financial year ending March 2024. Dharma? Just 60 lakhs.

That’s not a typo. Dharma, with all its legacy and star power, earned less in profit than what it probably spent on vanity vans for a single movie. Their operating margin plummeted from 13.4% in 2022 to -0.5% in 2024.

“Everybody thinks the bigger the film, the bigger the money made, but that’s not true,” Johar said at the CNBC-TV18 Global Leadership Summit after selling the stake.

Take Brahmāstra, Dharma’s biggest bet in recent years. It grossed ₹420 crore—but cost ₹400 crore. After sharing its razor-thin profits with funding partners, what was left? On paper, a hit. On balance sheets, not much.

Meanwhile, Maddock was perfecting a different formula. They kept budgets controlled, focused on storytelling, and operated debt-free. Stree (2018) made for ₹30 crore, earned ₹167 crore. Munjya (2024) also cost around ₹30 crore and brought back ₹120 crore. These turned out as financial masterclasses, not merely box office hits.

That difference is clear in their margins. In the latest numbers, Maddock operates with a 20.9% profit margin. Dharma? 0.1%.

"With big films, the journey to recovery is often long and the margins aren’t very large," Johar admitted. "But when you make a film in the ₹65 crore to ₹80 crore window and you really hit a large number, that is the film I’m chasing. More than the tent-pole film, I’m chasing the middle-budget film that gives me the larger return."

The returns make this clear: The Kerala Story turned ₹15 crore into ₹286 crore—a 19.1x return. Compare this to Tiger 3, which made ₹464 crore on a ₹300 crore budget—just 1.5x.

"When you actually bring a good product to your audience, and you don’t pretend that your audience is stupid, then it will make that kind of money," Shreemi Verma, a creative producer and screenwriter told me. "Maybe it won’t make it on the first Friday itself, but if you let it remain in theatres, it will make it."

The point is, there’s no one way to make films. A ₹25 crore film can be as viable as a ₹250 crore one—if it’s made for the right audience at the right price.

Hindi cinema’s audience stretches from South Bombay to Indore, from Gurgaon multiplexes to single screens in Ranchi. They deserve stories as diverse as they are—stories of different scales, for different sensibilities, across different price points.

Look at Oppenheimer: a three-hour drama about quantum physics made ₹150 crore in India. It wasn’t a mass entertainer, yet it found its audience—because in a country this big, different kinds of films can work. Even a fraction of India’s theatrical audience is enough to make a film successful.

Reminder again: when just 30 lakh people—barely 3% of Hindi cinema’s core audience of 9.2 crore—can generate ₹60 crore at the box office, the economics of mid-budget films prove both sustainable and profitable.

“We have to recalibrate these pay scales, and we have to tell all kinds of stories,” Zoya Akhtar said at THR India roundtable.

“Everybody cannot start making horror comedies,” she added, possibly pointing to the runaway success of Stree 2 and Munjiya. “We are the largest filmmaking nation in the world, and we have to tell all kinds of stories. And we are a diverse nation. We have to represent everybody in our films.”

But this can’t happen when every film is designed to be an event, when every release is burdened with the pressure of breaking records. In trying to make every film for everyone, we risk making films that truly speak to no one.

The industry’s greatest trap isn’t failed experiments. It’s the reluctance to experiment at all—and making experiments (and failure) more costly. In trying to make an inherently uncertain business artificially certain, Bollywood has boxed itself into creative constraints that breed mediocrity.

At its core, the crisis extends beyond financial risk to reveal the industry's deeper confusion between managing risk and avoiding it altogether. And in that avoidance, it overlooks what truly matters.

"Why and how a film is made is something which has no rule," says Navjot Gulati, writer-director of the show Industry. "The reason a film gets made is not because of that script. It is always something else. And that something else is not defined. It can be random. For instance, there could be a man with money and he owes a favor to someone."

Through years of observing how films get made in Bollywood, Gulati sees one constant truth: "If there is a story or a film which one person is dying to tell—it can be the writer, director, actor, or producer—if somebody is really dying to tell a story and puts their whole mind and soul behind it and fights to protect that film through the process of making, we’ll always end up with a film which is good."

The numbers should serve the stories, not dictate them. Because when you find that rare alignment—where the budget makes sense and the story demands to be told—that’s when cinema truly works.

Footnotes

- Most of the data on audience trends and broad cinema dynamics come from our review of reports by Ormax Media. All sources are linked wherever referred.

- It's hard to get definitive data on box office collections—there is no single authoritative source. For analytical purposes and consistency, we referred to numbers from Sacnilk. In a few instances where data was not available (especially for recent films), we relied on news reports. All numbers are used to give readers a sense of the movie industry's economics and how it functions—ranges matter more than exact counts.

- Films have other revenue streams—streaming, TV rights, music, and ticket sales in overseas markets. For this analysis, which was primarily focused on Hindi cinegoers, we accounted for India gross box office figures only.

For feedback and comments, write to the editor at samarth@theplankmag.com