I. The Alert

In 2021, Lucknow’s police described a future where crimes against women could be stopped before they began.

CCTV cameras would be installed across Uttar Pradesh’s capital city. Two hundred ‘harassment hotspots’ were selected based on years of complaints. The cameras on those locations would scan faces continuously.

But these won't be like the traditional cameras in my residential vicinity—the same ones I desperately needed when my pet cat went missing. They just watch. Lucknow’s new cameras would be intelligent—artificially intelligent.

Their algorithms would search for the telltale signs of fear—a flash of widened eyes, lifted eyebrows, tensed jaw muscles—that appear and vanish in seconds. They would infer emotional state from changes in facial expressions. When they detect distress, an alert would hit the nearest police patrol, promising help before crime could unfold.

This project was part of ‘Mission Shakti,’ a women’s safety program launched in October 2020.1 The intent seemed noble: a societal problem was acknowledged, a technological solution was proposed.

I learned about this program in June 2024, and my scepticism ran deep. As a technology researcher who had filed close to a hundred Right to Information requests investigating government AI projects in the past year, I recognised a familiar pattern: grand promises built more on hype than reality.

In Maddukarrai, officials proudly announced AI preventing elephant deaths—what they really have are humans watching thermal camera feeds. Northeast Frontier Railways went further, installing an AI solution for drowsy drivers: the system apparently monitors their blinking and applies emergency brakes when it catches train drivers mid-yawn. (One imagines the satisfaction of explaining why the train stopped to passengers.)

These might seem like amusing outliers, but India’s ongoing romance with AI runs deep. In March 2024, Prime Minister Narendra Modi declared at the Start-up Mahakumbh:

“We are in a new era of AI technology… India will have the upper hand in AI… and it is our priority to ensure we do not let go of this opportunity”

The message to departments was clear: pilot AI projects, generate media coverage, and align with the national vision. And so they did, from AI news anchors to chatbots for farmers’ welfare entitlements.

What makes the current moment different is that AI has evolved from simple statistical rules into something more unsettling—perhaps a mirror of human cognition. What once seemed impossible—machines that could chat like old friends and create artwork from text descriptions—is now commonplace. But could it really prevent crime?

I had to know: How is Lucknow’s system actually working? How are artificial eyes scanning for trouble? How does an algorithm distinguish between a woman’s genuine distress and a momentary frown?

This was a project combining surveillance, artificial intelligence, and police response that could reshape how Indian cities approach women’s safety. So I boarded a train to Lucknow to see this system for myself.

II. The Screen

On a sweltering September afternoon, I was shifting uncomfortably in a rickshaw, its seat scalding hot with exposed spongy interiors, on my way to Mahanagar—home of the Crime Branch of the Lucknow Police Commissionerate. I found Deputy Commissioner (Crime) Kamlesh Kumar Dixit’s contact on the UP Police website and cold-called him to request an interview. “I’ve heard and read a lot about your department's tech-savvy projects in the media and want to know more,” I said. He welcomed my curiosity. I knocked on his door 45 minutes later.

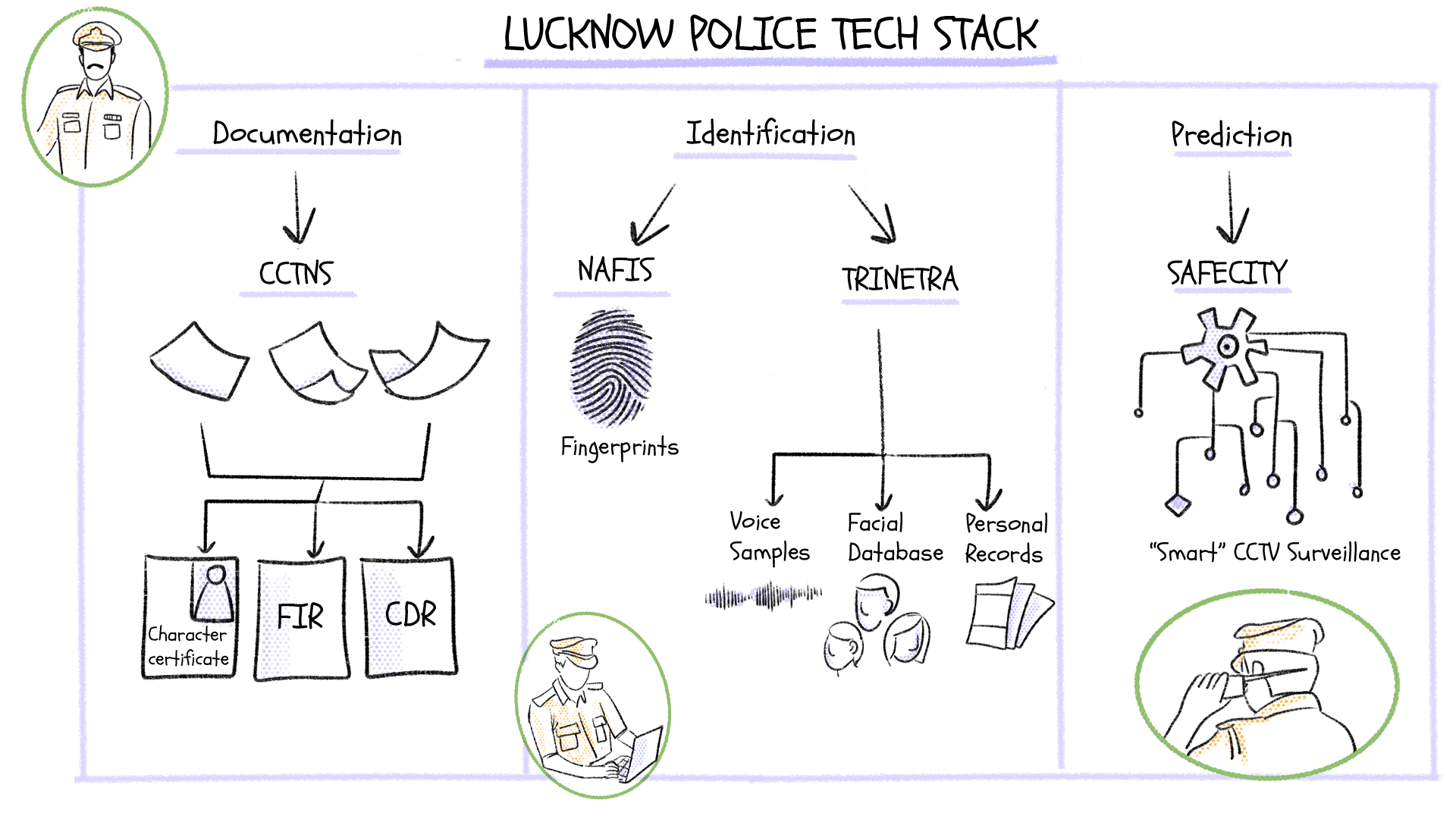

He pointed me to a seat, and before we exchanged words, signalled his staff to bring me a cup of chai. For the next hour, I asked Dixit about his department's journey into digital policing. He walked me through their arsenal: Trinetra, their facial recognition database that could run and match any suspect’s face with a vast criminal database; their good old Crime and Criminal Tracking Network and Systems (CCTNS) to digitise FIRs; and the new biometric profiling database, the National Automated Fingerprint Identification System (NAFIS).

I waited patiently, taking notes, anticipating the moment he would mention the project that had brought me to Lucknow. And then, Dixit suddenly straightened in his chair, his eyes glinting and voice brightening: “And not to forget, Our ‘Safe City’ project has 1200 AI cameras across Lucknow to detect crime and alert the police.”

My ears perked up. “Sir, is this where you monitor expressions of women to detect distress?”

“You can ask the Safe City team,” Dixit said, seeming unclear on the mechanistic details. He quickly reached for his phone with visible interest, reading out my visiting card details to someone on the other end. “You should visit the Safe City Control Room now… an inspector will drive you.”

The inspector’s SUV muscled through thick traffic and narrow market streets of Lalbagh, finally pulling into a spacious cement lot with two nondescript buildings. One sign read “Swachh Lucknow Abhiyan,” another “Safe City Control Room”2.

I climbed to the third floor where a beaming young man met me by the stairs. Ankit Sharma, he introduced himself, a Manager at Allied Digital Services3, which built the technology powering the Safe City Project. He gestured at my feet—shoes off—and led me toward the control room. After all the media stories and speculation, here I finally was, about to see the reality of Lucknow’s AI experiment.

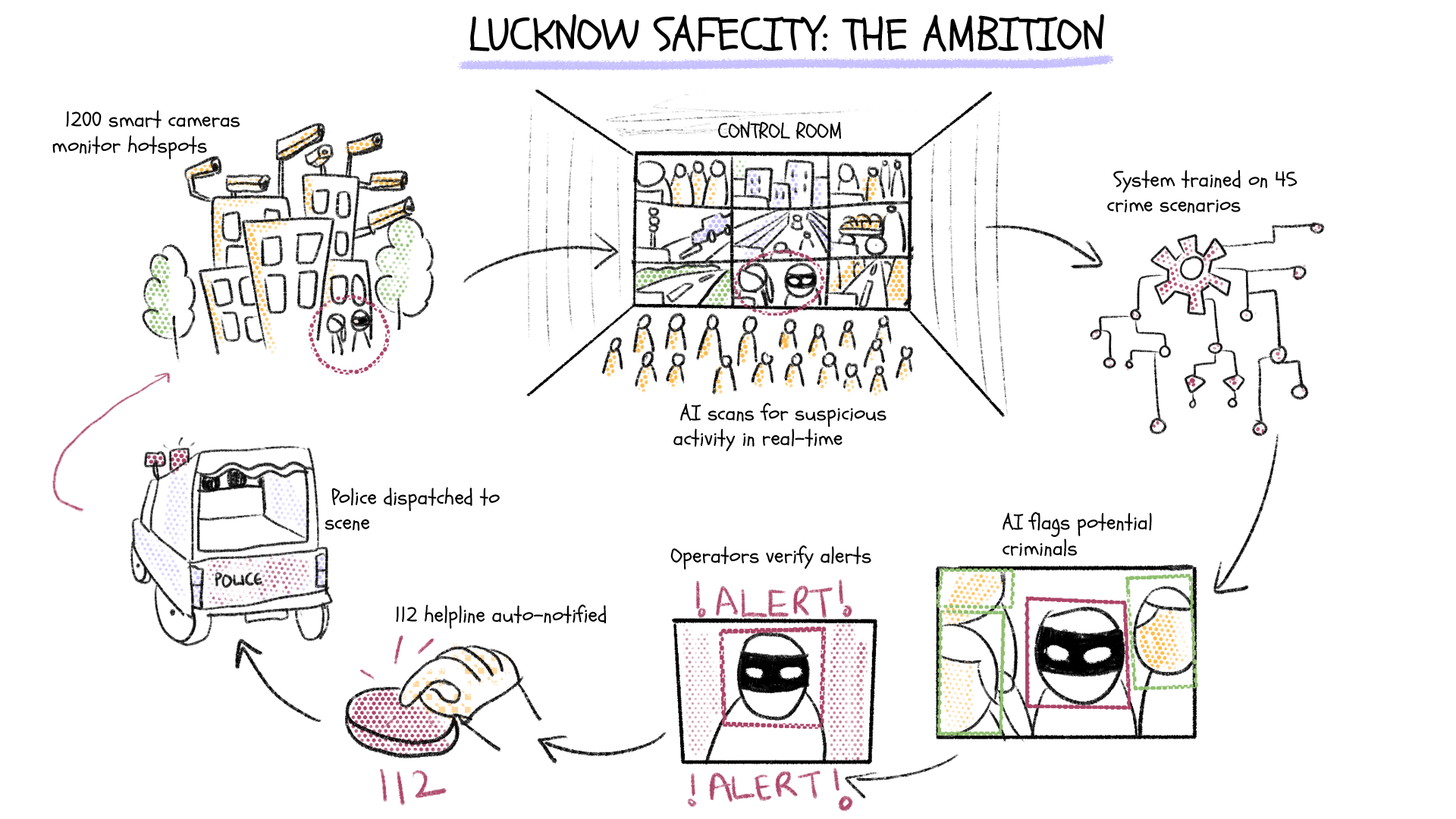

The Integrated Smart Control Room, or ISCR, overwhelms you before you understand it. A massive LED screen dominates what feels like a hospital ward. On it, analytics pulse and flutter: numbers, percentages, and data cascading in real-time. Everything moves. Everything is alive.

Live feeds from any 9 out of the 1200 AI-enabled CCTV cameras in the city run on the left half, and real-time facial recognition software scanning unsuspecting pedestrians—tagged with age and gender—is splashing on the right half. Faces refresh every five to eight seconds. As I sat and absorbed the sheer scale of operations in the freezing cold room, I was handed my mandatory cup of chai.

The technology wasn’t revolutionary—it’s the same facial recognition technology our phones use—but the scale makes it feel like science fiction. I’m watching actual people, right now, walking Lucknow’s streets, unknowingly being dissected by algorithms.

It's like sitting in the front row of an IMAX theatre, but there's only that one row. Too close. Too much. I step backwards to the end of the room, trying to take it all in at once. The word that keeps coming back is “overwhelming.”

At that point, when I asked about the emotional distress detection project, Ankit frowned. “What is this? There is no such project. That would be stupid—emotion recognition isn't even accurate technology. Who told you about this?”

Standing there, watching the cascade of data and faces, I realised two things: My suspicion about the emotion detection project was correct. It didn’t exist. Because it can’t exist: there is just no evidence that shows facial expressions can reveal a person’s feelings—the idea in itself was rooted in pseudoscience, a myth sold to police departments and parroted to the media.

But then, I also realised, something much bigger was unfolding in this room. Instead of scanning women’s faces for distress, Lucknow had built a system to detect potential perpetrators’ physical movements—a surveillance network that could track patterns of stalking, harassment, and assault in real time.

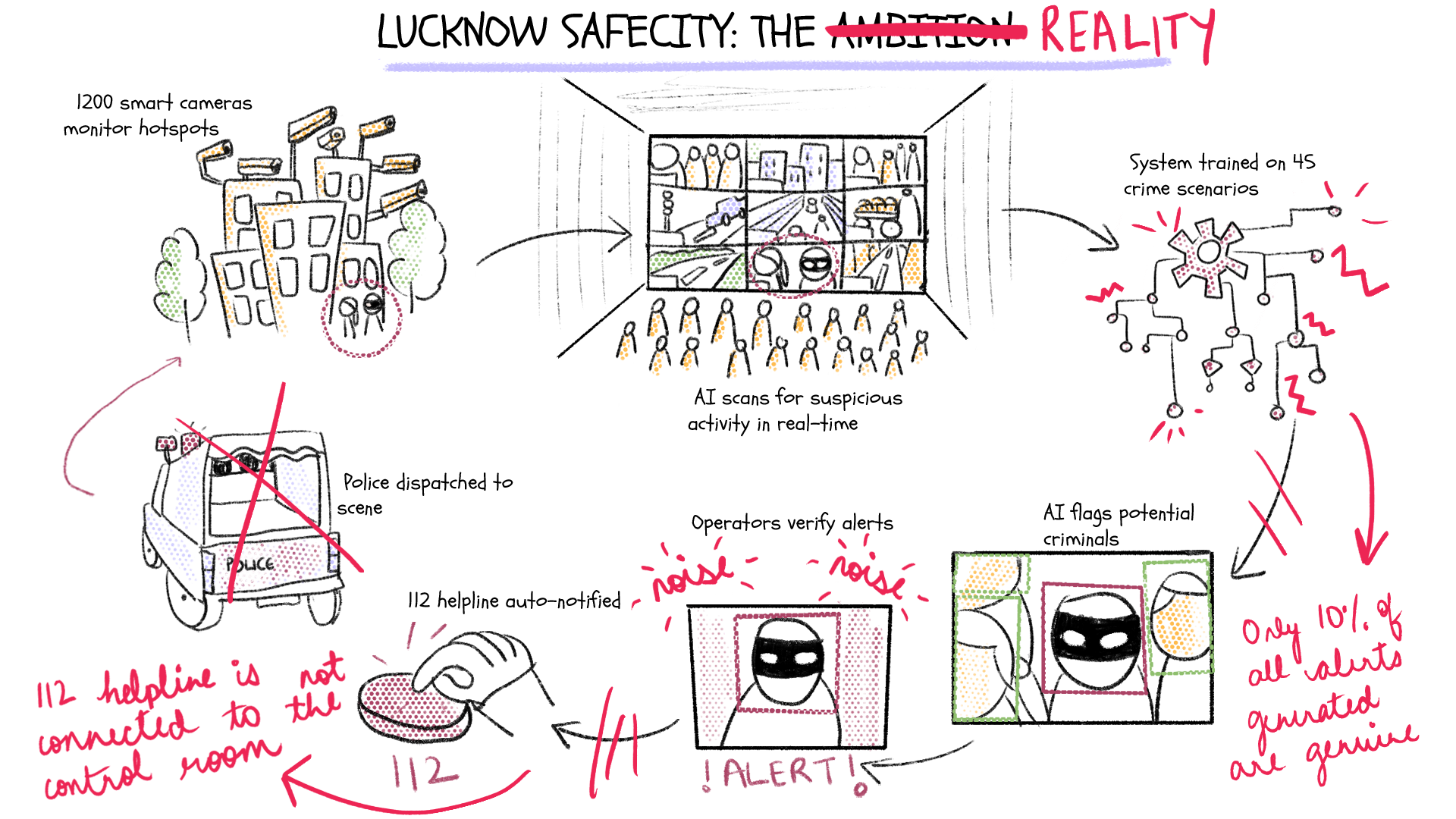

This was one piece of India’s larger Safe City program, launched across eight major cities in 2018.4 Lucknow’s pilot started in 2022.

The vision remained the same as the emotion detection project: stop crimes before they happen. When the 1200 AI cameras detect suspicious activity, they instantly generate an alert. One of the 40-odd employees validates the CCTV footage. If they confirm a crime, the information goes to Uttar Pradesh’s centralised 112 emergency control room5, which dispatches police officers to the scene.

This project is funded by the Nirbhaya Fund, which was established in 2015 in response to the brutal 2012 Delhi gang rape case. Upto the financial year 2023-24, around ₹7,000 crores has been allocated to various projects. Nearly a quarter—₹1,600 crore—went to Safe City projects across India. And, as Ankit told me, ₹98 crore—almost half of Lucknow's total Safe City budget—was invested in this single room and its network of AI-enabled cameras.

“We introduced AI to Lucknow to help people,” Ankit said proudly while giving me a tour of the space.

What exactly were these algorithms detecting? How did it actually work in practice?

III. The System

Allied LLC was tasked with building Lucknow's Safe City network from the ground up. They would provide everything: the equipment, the software, and most importantly, the AI. To teach their smart cameras what to look for, Allied had trained their system on 45 different crime scenarios provided by Lucknow police—a list that read like a catalogue of urban fears, each item revealing how police imagine crime unfolding in public spaces.

The cameras would watch for the obvious violence: fights, slaps, hair-pulling, faces being blackened with ink. But they would also detect subtler threats: men lurking in “shadow areas,” groups smoking near women’s colleges, suspicious lingering outside ladies’ markets. They would track vehicles cutting lanes erratically (potential kidnappers), monitor men’s behaviour near public toilets, and scan for registered sex offenders walking the streets.

Some scenarios were unnervingly specific: women waving desperately from auto-rickshaws, unconscious bodies in dark hours, and unattended bags near hospitals that might hide evidence of female infanticide.

Ankit walks me through this system for ninety minutes. He has a curated folder of success stories—videos where the AI does exactly what it’s supposed to do. People move through frames surrounded by coloured boxes: red for suspicious, green for normal.

“The key is teaching AI what not to flag,” he explained, as he pulled up the demo videos on the screen and gestured to a computer operator: “Arrey woh nahi, acid bottle wala dikhao madam ko [No, not that one, show madam the acid bottle clip].” I leaned in closer.

We don’t want alerts for every bottle in the frame, he said, gesturing at a crowded street scene. The AI looks for a specific grip. His finger traced the image of a man’s hand wrapped around a bottle’s neck—the only way to grip when acid heats up the rest of the bottle. What stunned me was watching the system ignore other bottles in the same frame: ones tucked in bags, carried casually or held normally. Only the potential weapon drew a red circle, tracking its movement across the screen.

In this demo, the technology’s ability to distinguish between innocent and threatening gestures was both impressive and chilling. Here was an AI that claimed to recognise human intent in the position of fingers around glass.

“The system is working,” Ankit insists, pointing to his evidence.

“The system is working,” I repeat silently, mesmerised and unsettled with his carefully selected clips.

But the very perfection of these demonstrations raises questions. How often does this happen in real-time? How many crimes has this machine actually prevented?

This is where the curtain falls on the grand vision. The system generates 700 alerts a month, Ankit told me—of which 90 per cent are false positives6, meaning nine out of ten alerts flag innocent actions as threats. Which means 70 genuine alerts monthly. Or just two identified threats a day—accompanied by 20 false alarms pointing to non-existent threats.

Is that intelligent surveillance? Or just digital noise?

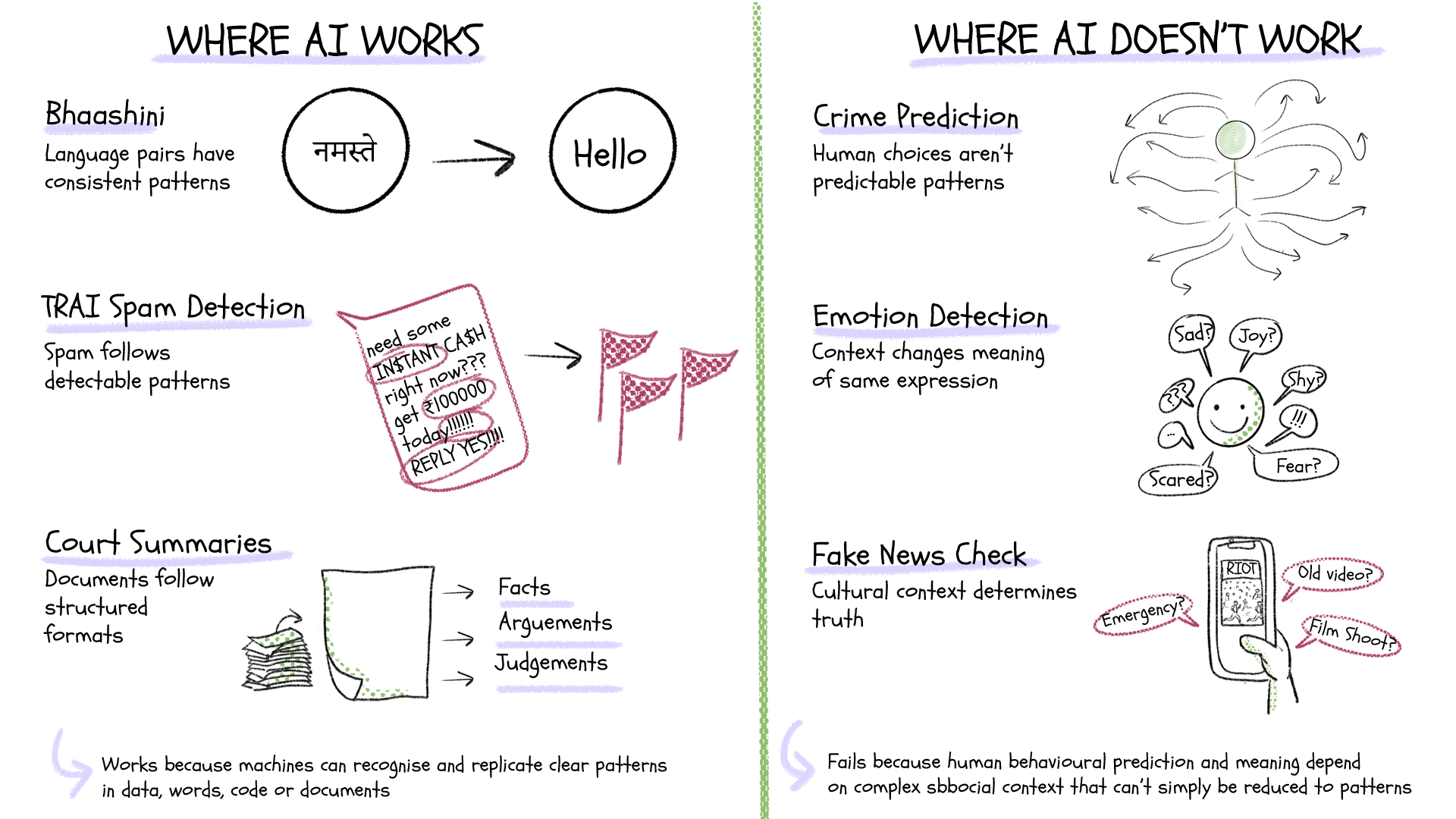

The gap between this demo and reality exposed a key distinction I had read in the book ‘AI Snake Oil’ by Arvind Narayanan and Sayash Kapoor. They separate AI into two broad types: generative AI, which has made remarkable breakthroughs in tasks with clear rules and patterns, and predictive AI, which attempts to forecast human behaviour.

The first excels—it can write code because programming follows precise logic, generate images because it learns from millions of examples of what things should look like.

But predicting human behaviour—especially criminal intent—is fundamentally different. An AI can analyse millions of images to learn what a “suspicious person” looks like in general, but a person who looks suspicious may be innocent, and a criminal may look ordinary. Intent can’t be captured in patterns.

Take Ankit's bottle detection demo: in a controlled test, AI might spot the difference between a weapon and grocery. But in the messy reality of city streets, where context changes everything, even this simple task becomes unreliable. A father waiting outside a school holding his son’s water bottle might trigger an alert, while an actual perpetrator could carry acid in a soft drink can. Context isn’t just about the grip—it’s about the invisible human stories that the cameras and their algorithms can’t see through.

Yet this reality hasn’t deterred the optimism. Their point isn’t that it works now, but that it will work. Someday. Eventually. It’s a promise perpetually set in the future tense—one that justified setting aside around a hundred crores from the Nirbhaya Fund.

Even DCP Dixit, for all his candour about his force’s capabilities, frames it as a matter of time. Most tech projects in the Crime Branch were introduced in 2022, he explains, and haven’t had enough time to mature. The newness of the technology becomes both an explanation and an excuse for its current shortcomings.

When asked about potential challenges to his future-perfect system, Ankit mentioned only one concern: Lucknow’s air pollution might cloud the cameras’ vision. “But it's okay,” he added reassuringly, “we have applied for funding to get all cameras cleaned twice or thrice a week.”

I pressed further, asking about possible biases, gaps, or risks. He waved off my concerns: “The AI will only get stronger as it trains on more pedestrian faces... it needs time with large volumes of data to enhance accuracy, so there will be no bias.”

Then came the most revealing detail: the system-generated alerts weren’t even automatically reaching the 112 emergency helpline. This wasn’t a minor technical gap—the entire system was designed around 112 operators analysing video footage, pinpointing crime locations, and dispatching police teams to stop crime before it occurred.

That was the whole point—and yet, in close to two years of operation, no linking had happened. Instead, control room staff were simply calling local police stations.

The gap isn’t just in the algorithm’s capabilities but in the basic plumbing of the police response. We’re so caught up in making the AI work, in debating ethical questions of bias and technical questions of accuracy, that we often neglect to ask what happens if and when it does. Are women safer, or just more surveilled?

These answers, I knew, wouldn't be found in this control room with its pulsing screens. They were out there—in the police stations, where Safe City’s alerts were supposed to connect with reality.

IV. The Station

Three kilometres away, at the Daliganj police station, three officers hover around a computer screen, their frustration mounting, as I sip on my hundredth chai of the week. They can’t get past the login screen of Trinetra, the police force's sophisticated AI-based facial recognition system built by Staqu Technologies7.

“Should we call him at home?” one suggests. They debate the propriety of interrupting their IT operator’s day off just to ask how to log in. He’s the only person among 150 officers at the Daliganj thana who knows how to operate the system. Finally, they dial. He relents.

When we finally access Trinetra, reality deflates the promise. Instead of the advanced crime-fighting tool trumpeted in media reports, what appears is almost anticlimactic: an unassuming landing page showing 31,000 FIR records spanning two years. Many records lack photographs. Clicking through to a criminal profile—one “Aman”—reveals three photos from different angles, basic personal details, an Aadhaar copy, FIR information, and a voice sample.

I asked if this interface connects to any other criminal databases, or at least to the central FIR and criminal repository, the CCTNS8. The officers shake their heads no.

“Is this it?” I ask. “This is it,” they confirm.

This was Trinetra—the system that was supposed to revolutionise criminal search across Uttar Pradesh, tracking suspects through facial recognition. But all I was looking at was just a digital filing cabinet with incomplete records.

“Could I see how facial recognition works?” I ask. They explain I’d need the smartphone app for that feature.

“Could I download the app?” I naively ask as the officers exchange glances. It turns out most of them can't either—officers below administrative ranks don't get login credentials. Some don't even have smartphones.

And those few who do have both phone and access face an even more fundamental problem: accuracy.

“This is not very useful,” Sub-inspector Ashish Yadav tells me, his frustration evident. He's a young, confident officer who's given media interviews about police reform, but here, in the station, he's remarkably candid about the system's limitations.

“When we are told to use Trinetra, if we can get access to search for a criminal by their photo, it gives us 25-30 results which look nothing like the picture,” he added. “When we search using a name, it does not show us results for other similar-sounding names,” he said, explaining how this remains a problem given the diversity of spellings in Indian names. He laughingly recalls several stories of the system churning out irrelevant results when seniors demanded Trinetra’s use, then pauses to request I keep those off the record. (Trust me—hilarious.)

“We have many other ways of getting the same information from criminals about their associates in a much shorter time,” added Inspector Ashok Kumar, his desk and walls speckled with photos of and quotes from Babasaheb Ambedkar, as he gestured at staff to get me another chai. “Once we get them to the chowki, we use our questioning and policing skills to get all the information we need.”

Ashish’s simple articulation of how unaffected and removed he is from these tools had a profound impact on my understanding of Lucknow Safe City. “We don’t need these technologies and we don’t always have time to go online and use them. We would rather be doing real police things.”

It’s not that the officers are opposed to technology—they're desperate for it to work. The CCTNS Cell in Lucknow, which maintains the digital log of all FIRs and criminal records, hasn't hired new IT staff since its establishment in 2014. They have been requesting basic features for years: a simple search function, a simply automated system for character certificate verification to cut manual processing time, and faster (rather, normal speed) servers.

They want charge sheets and trial verdicts automatically synced so acquitted people can be removed from the database. “We are worried that there are too many innocent people on the database,” they told me.

The irony is clear: the Lucknow police know exactly what digital tools would make them more efficient. But instead of addressing these basic needs, the state’s response to these fundamental gaps is, predictably, more technology—expensive ‘cutting-edge’ projects they never asked for. Each new AI system promises to fill the gaps left by its predecessors, aggregating into an ever-expanding architecture of surveillance.

When I asked officers about working with the new Safe City project, one joked, “Making Lucknow a safe city is not a new project, it has been our job for many decades.”

V. The Circle

As I reported this story, trying to make sense of a ~100-crore system generating just two genuine alerts a day, I wondered about our priorities.

A third of all crimes against women in India are domestic9—which no cameras can spot. Women across India still experience persistent difficulties in filing police complaints. Community shelters that provide legal and medical assistance to assault victims remain understaffed and underfunded.

These are hard problems. But here we are, pouring resources into watching public spaces—not because it's the most effective solution, but because it's the most technologically feasible.

And yet, the logic of surveillance seems irrefutable: if someone is watching, people behave better. We install cameras outside our homes, in shops, in schools. When my own cat went missing, I instinctively requested access to ten CCTV feeds to quell my worries. The belief in watching as deterrence runs so deep that it feels like common sense. Who wants to be the person who said "no" to a system that might have prevented an assault?

That's the trap: technology presents itself as the solution to an urgent problem—in this case, women's safety. The trade-offs—normalised monitoring and loss of privacy—become necessary compromises. Those questioning surveillance must prove it won't prevent harm—an impossible task—while those promoting it need only gesture at potential benefits.

Back at the Safe City control room, Ankit speaks of his AI as infallible, with "infinite scalability." Though trained to detect crime, it now picks up potholes, traffic patterns, and construction sites. During the Ayodhya Ram Temple consecration, the algorithms running in the control room provided traffic management services.

“All this information can be packaged and provided to urban planning authorities,” he beams.

Allied, his company, is already planning their next AI-based solution—a gesture-based emergency prompt using the cameras. Lucknow can’t detect women's distressed emotions, and so, perhaps, their answer is simpler: any woman in trouble can simply look into one of their smart cameras and wave both hands above her head to signal for help.

We reached out to Paresh Shah (CEO, Allied Digital Services LLC), Atul Rai (CEO, Staqu Technologies Ltd), and Inderjit Singh (CEO, Lucknow Smart City Ltd) with questions and requests for comments but did not receive a reply. We believe in fairness, and we shall update the story if we receive a response.

For feedback and comments, write to the editor at samarth@theplankmag.com

- Mission Shakti is a women’s welfare scheme set up by the Union Ministry of Women & Child Development in response to the 2012 Delhi gang rape. It has a number of subsidiary projects for self-help, financial literacy, education, empowerment, and women’s safety. State governments implement the mission locally and can adapt it to regional contexts. ↑

- The Lucknow Safe City Project has multiple services: pink (women-only) buses and their own CCTV network, pink (women-only) public toilets, the 112 emergency helpline to report crime, Asha Jyoti Kendras (community centres for support), pink patrol vehicles manned by female police officers, the 1090 local police helpline, drones, mobile CCTV vans, and the Smart City office. The project's cornerstone is a network of 1200 AI-enabled cameras strategically placed across the city: 200 with pan-tilt-zoom (PTZ) capability, 200 inside pink buses, and 800 fixed-pole mounted units. ↑

- Allied Digital Services LLC builds digital solutions and IT platforms for a diverse range of public and private clients. Their most prominent government projects are Smart City and urban surveillance systems in Pune and Lucknow. ↑

- The Safe City project, launched in September 2018, aims to protect women in major metropolitan cities across India. The initiative began with pilots in eight cities: Ahmedabad, Bangalore, Chennai, Delhi, Hyderabad, Kolkata, Mumbai, and Lucknow. While the selection criteria for these cities remains unclear, the Ministry of Home Affairs designed the program to focus on women's safety in public spaces through surveillance and emergency response systems. ↑

- The 112 emergency helpline is India’s integrated response system for police, fire, and medical emergencies, currently being implemented across states. Uttar Pradesh’s 112 is a matured emergency response center handling over 30,000 cases daily. On receiving a distress call, their operators triangulate the caller’s location and dispatch local police teams to the scene. ↑

- In multiple conversations, I requested month-wise statistics and official documentation of the crime alerts generated in the control room. Each request yielded a different response. I was informed no official documentation exists. Finally, via a WhatsApp message, I was told that the system generates an average of 700 alerts monthly, with a 90% false positive rate. ↑

- ‘Trinetra’ refers to a set of AI policing solutions developed by a Gurgaon-based private technology company, Staqu Technologies Ltd. and runs on their proprietary facial recognition software, JARVIS. In this story, we only refer to the facial recognition tool, also called Trinetra 1.0. With a mixed clientele of public and private agencies, Staqu is a popular collaborator with state home departments and is currently providing technological tools based on its JARVIS and SIMBA software to at least eight state police forces. ↑

- CCTNS has been an indispensable tool for police officers across India since its rollout in 2013. This is a central digital repository of FIRs and arrests made across states in India. FIR records are seeded at the district level by CCTNS Cells and stored interoperably in a central server. It does not store any facial or biometric data. It also acts as a citizen-facing resource to request character certificates from local police branches. ↑

- As per NCRB’s Crime in India report, the latest government publication on crime statistics, a majority of crimes against women registered under the IPC were under ‘Cruelty by Husband or His Relatives’ (31.4%) followed by ‘Kidnapping and Abduction of Women’ (19.2%), ‘Assault on Women with Intent to Outrage her Modesty’ (18.7%), and ‘Rape’ (7.1%). ↑